There are around 1200 rock-cut caves, which narrate India’s rich history. On the Western Ghats, 800 caves tell a story of the thriving Buddhist influence during the Mauryan and Gupta eras. Everyone is familiar with Ajanta and Ellora caves, but did you know that 24 km from Gaya, in the state of Bihar, on the twin hills of Barabar and Nagarjuni, are the Barabar caves, the oldest testaments of the lost Ajivika religious sect that once thrived in India?

Around 2500 years ago, during a period of religious reforms in India, Ajivikas emerged along with Buddhism and Jainism. The Indo-Gangetic plains were going through urbanisation. Independent republics ruled by hierarchical monarchs spawned a new generation of philosophers who embodied the ‘Sramana’ tradition. The Seramana mendicants were travelling mendicants who rejected traditional Vedic beliefs and travelled from place to place, espousing their ideologies.

Religious traditions that denounced the Vedas emerged as ‘nastika darsana’ or ‘heterodox philosophies.’ Jainism and Buddhism were among the religions that gained popularity and thrived into modern times. Makkhali Gosala, who founded the Ajivika sect, was a contemporary of Buddha and Mahavira, respective founders of Buddhism and Jainism. However, the Ajivika and many other traditions perished with the slipping sands of time.

Today, no Ajivika texts survive. The only shreds of evidence are the Buddhist and Jain text that mentions Gosala as one of the ‘six heretics’ and the inscriptions of Barabar caves. Buddhist and Jain sources paint Ajivikas negatively, condemning Gosala as a ‘Charlatan’ or a quack; Ajivika is portrayed as a rival tradition of Buddhism and Jainism.

Gosala used to be Mahavira’s companion, but the two had a fallout before Gosala went on his path. Gosala spent twenty-four years of his life as an ascetic and spent the first six years with Mahavira. After having parted, Gosala and Mahavira argued, and Gosala claimed that he was no longer the same man Mahavira once knew.

The original Gosala, it was believed, was a reincarnation of Udai Kundiyayaniya, an ascetic whose soul had passed seven bodies in succession before reanimating as the apparent Gosala.

The reincarnation theory was central to Ajivikas, who believed the fate of every soul is the passage through rigid ‘samsara.’ Fate, or ‘Niyati’, was one of the central tenets of the religious tradition. The followers of Gosala did not believe in free will—they thought that the past, present, and future are predetermined and can not be changed.

The concept of Niyati was popular amongst many belief systems of the time, and Ajivika’s theories gained massive popularity throughout India and beyond. Mahavamsha, the records of Sinhala kings of Sri Lanka, talks about King Pandukabhaya. It is said that the king constructed Ajivakanam Gruham (house of Ajivikas) at Anuradhapura, the capital of the time. By the 1st century BCE, Buddhism saw Ajivikas as a significant contender. The Barabar caves stand as a testimony to the widespread influence of the Mauryans during their time.

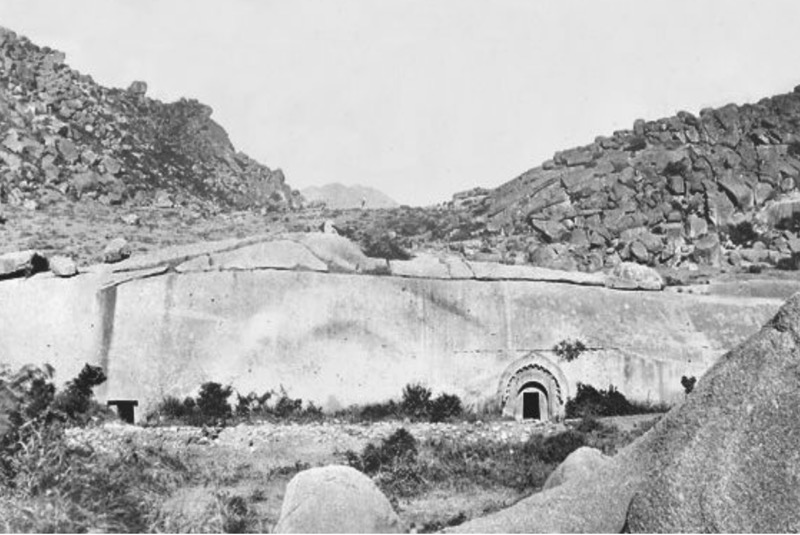

Dating back to the third century BC, the Barabar caves comprise seven caverns. They are the oldest rock-cut caves of the Mauryan empires. Four of them are on Barabar Hill, and three are in Nagarjuna. Locally, their names have been adapted from popular epics such as the Lomas Rishi Cave, Sudama Cave, and Vishwamitra Cave; however, these names have no historical implications.

Lomas Rishi Cave is the most popular and the oldest of all Barabar caves and is an architectural landmark for being the first to use the Mauryan ‘Chaitya arch’ in stone. Ajanta caves also use the same architectural designs as many other caves of the period. Later temples used the Chaitya arch as a decorative feature.

Each cave is made of granite and has two rooms with a polished “glass-like” surface, which came to be known as the ‘Mauryan polish.’ There are no idols or adornments in the room.

Some of the caves have clear inscriptions that hint at the kings who commissioned their constructions. For example, the Sudama cave inscriptions show that Asoka, the third Mauryan emperor, gave the caves on Barabar hill to the Ajivika monks in 261 BCE.

Inscriptions in the Nagarjuni caves provide evidence that suggests Ajivikas enjoyed protection and royal patronage during the Mauryan times. The caves of Nagarjuni hills are from the time of Dasaratha Maurya, Ashoka’s grandson.

There are no other rock-cut caves in India that can claim the same antiquity, and those from subsequent centuries provide a testament to the continuous evolution of technical competence and design on the part of their artisans. As a result, it is possible to argue that the Barabar caves reflect the origins of India’s rock-cut building heritage.

After the Mauryas, the Ajivikas saw a steady downfall and loss of popularity. They remained much longer in Southern India in comparison to the north. Ajivikas are mentioned in Silpattakam, the great epic of the Tamil language and thrived in Madurai. Manimekalai praises teachers of Vanji (near Kochi) who belonged to the Ajivika sect during the times of the Chera kingdom. However, by the Fifth century CE, the Ajivikas vanished.

Inscriptions on the Loma Rishi Cave indicate that Buddhist monks occupied the caves around 450 AD. Jains and Hindus are also known to have inhabited them at different times. Today, caves are among the popular places for tourists to visit. However, only a few would know the history behind them and the story they narrate of a once-thriving religion of India that is completely lost today.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]