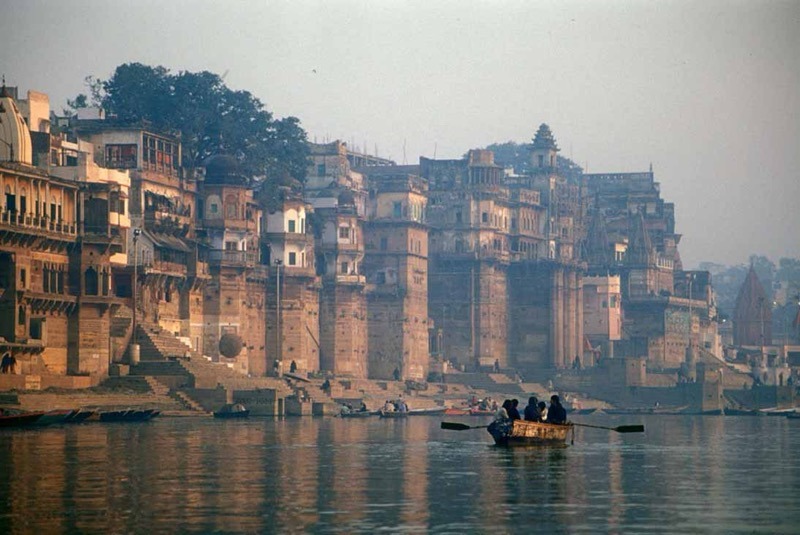

In the cool shadow of the Himalayas, where myth and geography intertwine, a river begins its descent through the heart of South Asia. For thousands of years, the Ganges has been a source of life, of spiritual renewal, of stories passed from generation to generation. Its waters, revered as sacred, have sustained the cities, farms, and forests of India and Bangladesh, supporting more people than any other river system on Earth. But now, something once unthinkable is happening: the river is drying.

This isn’t a subtle change, nor is it a seasonal quirk. The Ganges is shrinking in ways that scientists describe as without precedent in recorded history. Its tributaries are thinning, its beds are cracking, and the rhythm of the monsoon that has long replenished it is faltering. Across the basin—home to over 650 million people—the consequences are already visible in fields gone fallow, in empty canals, and in the deepening silence where boats once creaked and traders called across busy ports.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]