In 1917, Earnest Gilbert Meaton, a veterinary surgeon at Kolar Gold Fields, found a short, oval-shaped egg. Pale yellow in colour, it had brown and black blotches.

It was a rare find, and Meaton, who knew that the egg belonged to the Jerdon’s Courser, added it to his collection of bird eggs. However, he did not keep the Jerdon’s Courser egg with him. In 1919, he sold his entire collection of bird eggs to George Falconer Rose, a Scottish engineer, and entrepreneur based in Calcutta.

§§§

The Jerdon’s Courser is one of the rarest birds in the world, found only in Southern India. It is named after the British zoologist Thomas C Jerdon, who first collected a specimen of the bird–around 1844.

A committed ornithologist, Jerdon documented over 1008 species of birds in one of his books, the Birds of India (1862-64). In his voluminous tome, he listed the local name of Jordan’s Courser as ‘Adavi Utha-titti,’ meaning ‘jungle empty purse.’ He also gave it a scientific name–Cursorius bitorquatus. And when a specimen was presented to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, the curator, Edward Blyth, named it Macrotarsius rhinoptilus.

In later years, the Naturalist WT Blanford spotted the Jerdon’s Courser three times. In June 1900, the Northern Irish missionary Howard Campbell spotted it twice near the Pennar and Godavari river catchment areas in Andhra Pradesh.

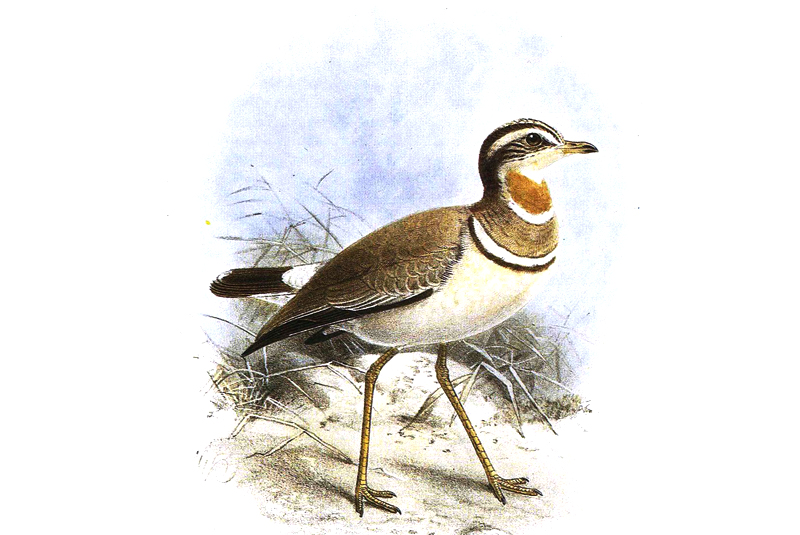

The species was not found again and the bird was presumed to be extinct. Consequently, very few people knew what the Jerdon’s Courser looked like, or how it sounded. Illustrations such as the one made by the Dutch bird illustrator John Gerrard Keulemans, created around 1888, were the only references.

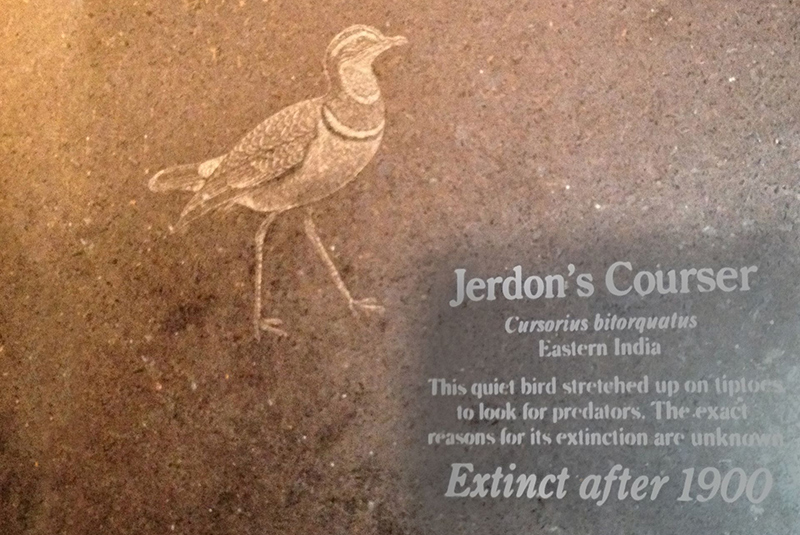

Though the bird was not spotted again, it was not forgotten by ornithology enthusiasts. It was considered so rare and precious that the Bronx zoo erected a tombstone with a chiselled image of the Jerdon’s Courser. It reads:

Jordan’s Courser

Cursorius bitorquatus

Eastern India

This quiet bird stretched up on tiptoes to look for predators. The exact reasons for its extinction are unknown.

Extinct after 1900

Almost eight decades later, in January 1986, a trapper near Reddipalli village in Andhra Pradesh found a bird which resembled the Jerdon’s Courser–a compact bird with two brown breast bands and a narrow white crown stripe on top of its head. Fortunately, he managed to catch the bird.

Soon, Bharat Bhushan, an ornithologist from the Bombay Natural History Society arrived to check its identity. Looking at its yellow base to the black bill, a blackish crown, broad buff supercilium, an orange chestnut patch near its throat and the unmistakable brown breast bands, Bharat Bhushan confirmed that the bird is indeed the Jerdon’s Courser.

A bird presumed to be extinct for nearly eighty-six years was found to be alive in the shrub jungles of Andhra Pradesh. A few others were also spotted around the area. It was an extraordinary discovery, one of a kind in the history of ornithology–a reason to celebrate.

Yet, there are many reasons to be cautious. Far from being secure, the Jerdon’s Courser faces a precarious future. It is listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – as critically endangered.

Today, the locals call it Kalivi Kodi, a vernacular name, markedly different from the one documented by Thomas Jerdon. Known by its scientific name, Rhinoptilus bitorquatus, the Jerdon’s Courser is considered to be a sister species of the Three-banded courser of Eastern Africa; its distribution is evidence of a former biotic link between peninsular India and the savanna habitats of eastern Africa.

Though the species was rediscovered three decades ago, not much is known about it. It’s elusive nature, and nocturnal habits make it difficult to spot and study their biology, distribution, and habits. Ornithologists have never seen its nest; we do not know about their exact population size, making it extremely difficult to protect them.

Researchers use automatic camera traps to study the bird. Thanks to this technology, there is photographic evidence of the bird. Tape surveys and tracking strips are also used to detect the footprints of passing birds. Thanks to its infrequent vocal calls at dawn and dusk, Simon Wooton, a researcher was able to record its distinct voice during a field trip. It’s the only known vocal recording of the Jerdon’s Courser – a series of staccato Twick-too…Twick-too… Twick-too or yak-wak.. yak-wak calls. You can listen to it below.

What is known, however, is that their habitat is extremely restricted, about fifty square kilometres. And, one of the significant threats to its survival is habitat destruction. The construction of a canal under the Telugu Ganga project posed a serious threat. More recently, illegal construction, shrub clearance for irrigation, and illegal cutting of red sanders pose a serious threat to their survival.

To counter this, scientists have suggested attempts to breed them in captivity by taking their eggs and hatching them under another bird with the scientific name R. Cintus. But there is one problem: no one has found a Jerdon’s Courser egg in the wild.

The only known specimen of a Jerdon’s Courser egg in the world is the one that Meaton sold to George Falconer in 1919. It’s in the Zoology Museum of the University of Aberdeen.

§§§

George Falconer, the Scottish entrepreneur who acquired the collection of bird eggs from Meaton, donated the egg collection to his alma mater, the Aberdeen Grammar School. From there, it was transferred to a storeroom in the Zoology Museum of the University of Aberdeen. It was found, by accident, when an academic was looking through the drawers of the museum. Using DNA analysis techniques, they confirmed that the pale yellowish egg with black and brown blotches is indeed a Jerdon’s Courser egg.

Looking at the bigger picture, some scientists suggest educating the locals (who currently look at it as a nuisance) and expanding the protected areas of prime habitat as an integrated recovery plan to bring back the Jerdon’s Courser. British academics from the University of Cambridge have come up with a plan to use the voice box with a photograph to track the bird and educate the locals. But the progress is very slow.

Either which way, one thing is clear. Regardless of the numerous ‘integrated plans,’ if the Government of India does not act fast in protecting the Jerdon’s Courser by restoring their habitat, we are at risk of losing this precious species–this time, forever.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to editor@madrascourier.com