It is estimated that only 5,000-10,000 of the world’s biggest animals, the blue whales, have survived whaling in the Southern Hemisphere. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, there used to be 350,000 before the pre-whaling period. This makes them some of the hardest to find. However, scientists discovered a new population of pygmy blue whales in the Indian Ocean.

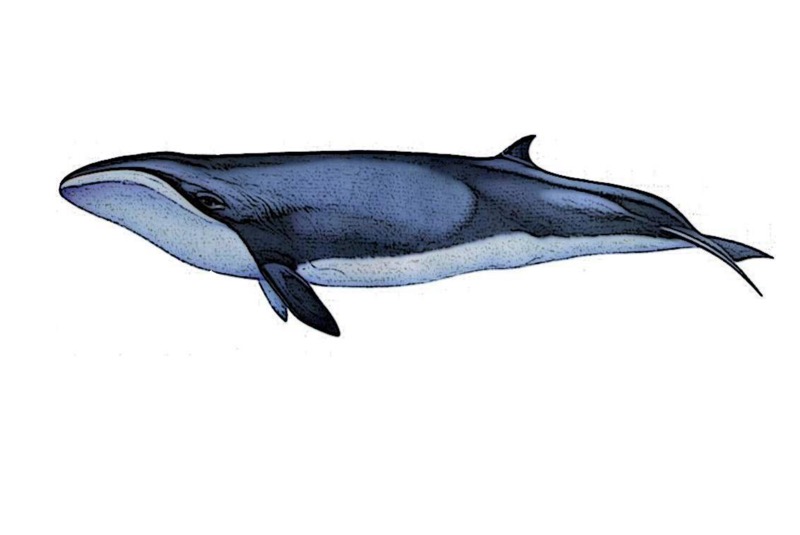

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is the biggest mammal ever known to exist. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries, these massive marine animals may grow to be 110 feet (34 metres) long and weigh at least 150 tonnes (136 metric tonnes). That’s almost twice the length of a school bus and three times the weight of a semi-trailer vehicle. And yet, they often go unnoticed due to their reclusive nature and their ability to cover vast areas of the ocean.

“Blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere are difficult to study because they live offshore and don’t jump around — they’re not show-ponies like the humpback whales,” says Tracey Rogers, a marine ecologist at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, Australia.

A group of scientists led by the UNSW Sydney is sure that they have discovered a new population of pygmy blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda), the smallest subspecies of blue whales in the Indian Ocean.

Pygmy blue whales are the tiniest members of the blue whale family, but that’s about it: they may grow up to 24 metres long, almost the length of two regular buses.

The study, which was published in Nature’s Scientific Reports, describes how the researchers discovered an entirely new population of blue whales by relying on data from the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), an international body that monitors international nuclear bomb testing, to detect the whales’ existence.

The CTBTO has been using advanced technology of underwater microphones, known as hydrophones, to detect sound waves from possible nuclear bomb testing. These recordings can capture a wide range of other detailed ocean noises and are accessible for scientists to utilise in their marine studies research.

The UNSW-led team was analysing the data when they discovered an exceptionally strong signal. It was a whale song that had previously been detected in the recordings, but scientists knew little about it.

Each group of blue whales has its unique song. The whales’ loud singing, recorded by underwater bomb detectors, revealed their presence. “Blue whale songs are very simple in the way that they are the repetition of the same pattern, but each blue whale subspecies and population has a different song type,” said Emmanuelle Leroy, a postdoctoral candidate at UNSW and the lead author of the study.

Blue whale songs are lengthy and low-frequency, often lower than 20 hertz, and cannot be perceived by the human ear. They are high-intensity and repetitive at regular intervals. However, different whale groups have sounds that vary in length, structure, and number of separate parts. “We still don’t know whether they’re born with their songs or whether they’ve learnt it,” said Rogers.

After analysing the song’s distinctive composition, such as frequency and tempo, found through the CTBTO data, it was realised that the whale population in the Indian Ocean had a unique song that had never been recorded. Dr Leroy compared the song’s acoustic characteristics to three other blue whale song types known in the Indian Ocean. She even compared it to four kinds of Omura’s whale songs, another prevalent whale population in the region, and yet the evidence pointed to this being an altogether new population of blue whales.

“I think it’s pretty cool that the same system that keeps the world safe from nuclear bombs allows us to find new whale populations, which long-term can help us study the health of the marine environment,” said Professor Rogers, who co-authored the study. “Without these audio recordings, we’d have no idea there was this huge population of blue whales out in the middle of the equatorial Indian Ocean.”

At first, the scientists noticed many horizontal lines on the spectrogram, which represented a strong, energetic signal. To ensure it wasn’t just a “random blip,” the team scanned 18 years of CTBTO data. Rogers added that they found the song to be a dominant part of the soundscape in the region throughout those years.

The prevalence of the same songs makes the scientists believe that it is a whole new population rather than just a few individuals. Researchers still do not know the number of whales that comprise the group, but based on the sounds captured, they expect it to be a big number.

The scientists have called the newly discovered population “Chagos,” after the neighbouring island. They believe that the whales with the Chagos sound migrate across the Indian Ocean at various periods. As per Rogers, they have been tracked not just in the central Indian Ocean but also as far north as the Sri Lankan coastline and as far east as the Kimberley coast in northern Western Australia in the Indian Ocean.

Visual observations of such an elusive species may be difficult and costly to finance, so this is unlikely to be confirmed anytime soon. However, visual confirmation is a must to conclude such a finding.

“If it isn’t a blue whale, it definitely sings like one,” said Leroy. If visual observations confirm this new population, it will be the fifth pygmy blue whale population found in the Indian Ocean. “It increases the global population that we did not realise was there before,” says Rogers. The discovery is significant for marine conservation since whaling drove blue whales to the brink of extinction in the twentieth century.

Acoustic information in whale songs may also tell us about the animals’ geographical distribution, migratory habits, and population levels. Dr Leroy previously led a study that discovered blue whale songs change pitch in response to the cracking noise of the icebergs.

The findings of her current study, which analyses the change in the Chagos population over time, can reveal how the whales have adapted to warming ocean temperatures over 18 years. This study is also expected to uncover how they might progress in the future. “The largest animal in the world is one of the hardest ones to actually study,” says Rogers. However, Dr. Leroy admits that the first step to protecting the subspecies is through its discovery.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]