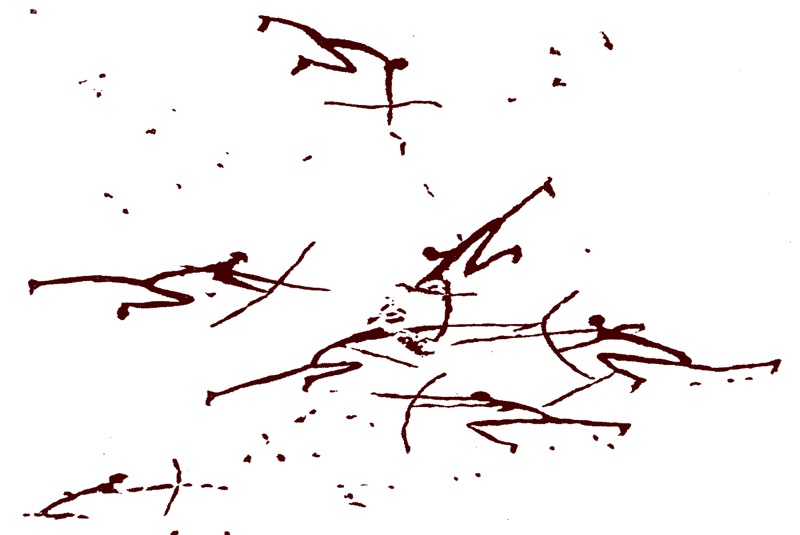

Jebel Sahaba is an ancient cemetery in Sudan, dated between 13,400 and 18,600 years ago. It is the earliest known evidence of frequent, small-scale disputes among human communities. In the 1960s, archaeologists discovered 61 skeletons in this Nile Valley area as the earliest evidence of mortal combat.

At the time, the fatalities were believed to be the consequence of a single-armed battle. However, recent research revealed that individuals buried at Jebel Sahaba did not fight in a single battle but rather in an early type of intermittent warfare characterised by recurring violence worsened by climate variations throughout the era.

The results, published in Scientific Reports on May 27th, expand on an earlier study into remains found in Jebel Sahaba. The study reframes hunter-gatherer conflict in the context of climate change, offering a fresh viewpoint on the evolution of violence and mass death in the Stone Age.

Between about 126,000 and 11,700 years ago, signs of human activity in the Nile Valley decreased dramatically. Hunter-gatherers inhabited floodplains in what is now southern Egypt and northern Sudan towards the end of that timespan. They were thought to have migrated from dry, less productive regions of Africa and southwest Asia.

As the Ice Age receded, a changing environment decreased good fishing and hunting locations; this was caused by extensive floods, upsetting the natural equilibrium. The researchers believe that competition for such resources sparked conflict among regional tribes.

According to Isabelle Crevecoeur, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Bordeaux in France, violence was a tangible part of existence. It arose through many raids, ambushes, and small conflicts caused by well-documented environmental shifts.

Christopher Stojanowski, an Arizona State University bioarchaeologist in Tempe, examined Jebel Sahaba’s remnants but did not participate in the current investigation. In an interview with Science News, he explained that the latest study fits into a scenario in which ancient, potentially culturally different tribes brutally invaded one another when diminishing resources endangered their existence.

For a long time, historians have debated whether violence began among Stone Age hunter-gatherers or in-state civilisations during the last 6,000 years. Isolated fossil instances of violence and murder stretch back about 430,000 years. As a result, the recent discoveries changed the history of violence in the Stone Age.

According to Crevecoeur and colleagues, 41 of the 61 Jebel Sahaba bones housed at the British Museum in London show at least one cured or unhealed injury. According to the experts, the bulk of the damage was inflicted by stone spears, arrow points, or close fighting. Weapon wounds on males, women, and children from Jebel Sahaba are of comparable kinds and sizes.

According to the researchers, most of the 132 stone items discovered in the Jebel Sahaba burials were fragments of the sharpened spear or arrow points. Some of these discoveries were lodged in bones and were surrounded by damage caused by forceful blows.

Microscopic examination also revealed that 16 individuals had both healed and unhealed injuries, implying that they had been subjected to repeated violent incidents throughout their lives. The researchers believe that the injury pattern was caused by periodic, indiscriminate raids rather than a single battle in which the dead would have primarily consisted of male fighters.

Previously, Marta Mirazón Lahr of the University of Cambridge led a team to study bone evidence from the Nataruk site in Kenya. It revealed a mass murder of 12 hunter-gatherers between 9,500 and 10,500 years ago. An assault by a neighbouring tribe best explains Nataruk’s injuries. According to Lahr, violence against this group was widespread and indiscriminate in terms of age and gender.

Ancient humans meticulously dug tombs at Jebel Sahaba for their deceased, interring corpses in identical, flexed positions. So, despite the seeming suffering, violence, and tragedy, Stojanowski pointed out the humanity within the community.

Lahr believes the bones discovered at the Nararuk site were too dispersed and broken up to have been deliberately buried. Stojanowski and his colleagues, on the other hand, believe that soil compaction after corpses were deliberately buried, most likely at various periods, may have caused damage to and dispersion of certain Nataruk bones.

According to Cal Poly Pomona archaeologist Mark Allen, it is difficult to accurately quantify the frequency of violent assaults among ancient hunter-gatherers in Africa and elsewhere. According to the latest Jebel Sahaba study, competition for scarce resources has historically resulted in deadly raids among these tribes. Allen and his colleagues discovered that skeletal evidence of violence among California hunter-gatherers increased during periods of resource shortage between 1,530 and 230 years ago.

Stone-age hunter-gatherer records provide insight into warfare and illustrate how climatic change, manifested as resource shortages, floods, and habitat loss, caused conflict and displacement. These climate changes, according to Crevecoeur, were not gradual. The people had to endure these traumatic transformations.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]