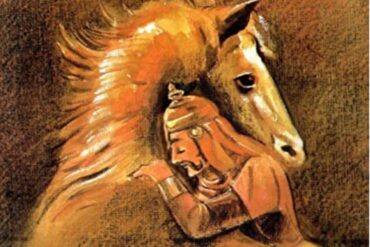

Hangul, the majestic stag, lives in the valleys and mountains of Kashmir. Believed to be the only subspecies of the European red deer in India, the Hangul is part of the only surviving subspecies of the elk.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies the Kashmiri Stag (Cervus Canadensis Hanglu) as a subspecies of the Central Asian Red Deer (Cervus Hanglu). However, Hangul is declining in numbers; it is listed as a critically endangered species by the IUCN Red List.

Ergo, the Government of India declared The Hangul among the top 15 high conservation priority species. The species has been classified in CITES Appendix I, Schedule I of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and Jammu and Kashmir Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1978.

Hangul, the state animal of Jammu and Kashmir, is found at the Dachigam National Park, fifteen kilometres from the state’s summer capital, Srinagar, where the animal is legally protected. Outside Kashmir Valley, these deer can also be found in the Northern Chamba district in Himachal Pradesh. However, they are not protected from hunting and poaching.

Hangul likes deciduous woodlands, highland moors, open mountainous regions above the tree line, and natural grasslands, pastures, and meadows. It favours mixed oak woodlands in the winter, followed by mulberry Morus and riverine settings. When the food is plentiful in summer, it prefers mixed oak forests and coniferous forests. It feeds primarily on shrubs and tree shoots in the forest, although it also eats grasses, sedges, and shrubs in other habitats.

The Hangul prefers mountainous areas; it spends the summers in alpine meadows and the winters in valleys. They like wooded slopes in the summer and grasslands on more flat ground in the winter.

According to studies, the Surfrao, Akhal, and Kangan blocks of the Sindh Forest Division are especially important for Hangul during the summer, when the upper subalpine parts of Dachigam National Park are under severe pressure from local people and livestock.

The population of Hangul has been periodically monitored at Dachigam since the early twentieth century. Before the partition of India, the Maharaja of Kashmir considered Hangul the ‘royal game’ and was strictly protected. However, soon after the partition of India and Pakistan, the numbers began to decline from 3,000-5,000 in the early 1900s to 180 in 1965.

The IUCN Red List mentions the Hangul as a ‘critically endangered’ species; only 100-150 mature individuals survive today. The entire Hangul population in the Dachigam National Park was estimated to be 110–130 in 2016. However, the number of adult individuals is probably much less. Due to questions about the reliability of official Hangul population figures and varying monitoring methods used throughout time, determining the population is extremely difficult. However, new evidence shows that the Hangul population will likely continue to decline.

The graceful Kashmiri stag is recognised for its distinct features. The deer have a bright rump patch that does not include the tail. It has a brown coat with speckling on the hair. The buttocks’ inside sides are greyish white, with a line on the inner sides of the thighs and black on the top side of the tail.

Males have splendid antlers with 11 to 16 points and long hair on their necks, but females have none of these characteristics. The brownish fur of the Kashmir Stag varies with season and age. The antler beam is firmly bent inward, and the brow and bez tines are generally close together and above the burr.

Poaching and illegal hunting are the biggest threats faced by these close-to-extinction species. Poaching by both civilian and military personnel has been identified as the primary cause of Hangul’s decline in the past and present.

The Wildlife Department is currently not patrolling and implementing protection activities adequately, owing in part to the occupation of Dachigam National Park by insurgents and armed forces. Poaching may have increased due to a lack of commitment from protected area staff.

The entrance of nomadic livestock herders and the predation of fawns by their guard dogs are also major issues that are not being handled adequately. Furthermore, livestock competition for grazing places and the risk of disease transfer are potential dangers to Hangul. Leopard and Asiatic Black Bear predation has been reported, which may aggravate an already precarious situation.

Local community involvement and improved knowledge in managing places where Hangul occurs will be required to curb the abovementioned problems. It is necessary for the long-term successful management and recovery of Hangul in addition to other conservative efforts.

The Hangul population in the Dachigam environment currently looks to have low genetic variation compared to other species, making it vulnerable to the consequences of inbreeding. A male-female ratio imbalance has been recorded. However, a population viability analysis (PVA) indicates that the population can recover if strict protection and other conservation measures are undertaken.

Despite Dachigam National Park’s conservation efforts, poaching remains the most serious risk to Hangul, threatening extinction. The highest priority conservation action is ensuring that poaching is no longer dangerous to Hangul. Preventing the entrance of nomadic livestock herders will minimise competition for grazing areas with cattle and reduce the possibility of disease transmission. It will most likely enhance fawn survival rates by minimising depredation by herding dogs.

Wildlife biologists propose expanding Hangul’s range. Enriching forest areas should give additional protection to their environment. Reducing the release of Leopards and Asiatic Black Bears in the region might also assist in minimising predation on Hangul fawns and boost survival and recruitment.

Conservation breeding is a high priority to protect the Hangul, increase recruitment, and possibly re-stock former localities, particularly the Overa Wildlife Sanctuary and Shikargah Conservation Reserve. They are ‘almost free of human interferences’ and have reportedly housed the largest Hangul populations in the past.

A Greater Dachigam ‘mega preserve’ has been proposed to improve protection in the Buffer Zone by improving conservation reserves and securing an Eco-sensitive Zone by protecting the surviving Shikargah subpopulations in the Tral and Sindh regions.

The Wildlife Conservation Fund (WCF) was founded in 2010 to conserve wildlife and wilderness in Jammu and Kashmir. They established the Hangul Conservation Project to preserve the Hangul population through community support, wildlife awareness, and wildlife management. It also aims to change people’s attitudes and foster harmonised living between humans and animals.

The project failed to achieve its goals since locals did not engage in the initiative. Furthermore, the project was limited to a 10-kilometer radius surrounding Dagwan. Ironically, the government authorities approved the construction of cement plants near the Dachigam National Park, which disrupted wildlife.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to editor@madrascourier.com