Mira Nair’s films have provided a subtle critique of Indian society’s social norms. Her movies, which remain relevant long after they’ve been released, makes one wonder if we are progressing as a society.

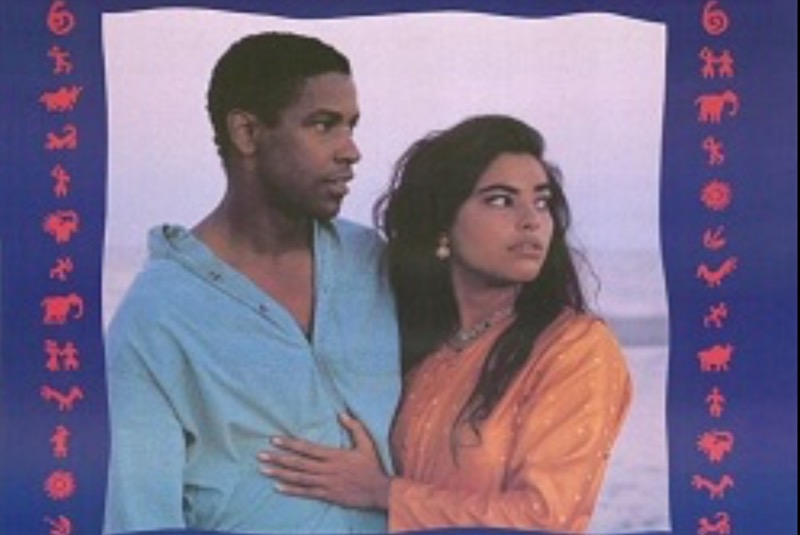

In 1991, Mississippi Masala hit the screens with a superb cast: Denzel Washington, Sarita Chaudhry, Roshan Chaudhry, and Sharmila Tagore. The film touched on many sensitive themes of the time, including the exodus of Indians from Uganda, the lives of Indians in American society, the complexity of romance for an interracial couple, and most importantly, anti-black racism in the Indian culture.

Set in the Deep South, a small town in Mississippi, the movie explores the tight-knit community of a diaspora of Indian motel owners. Since the 1940s, the motel industry in the United States has been operated by Indians. While Indians engaged with one another and formed a strong sense of community, they shut themselves off from assimilating into American society. Nair explores the issue of deep-rooted racism within the Indian community. She depicts how, despite shared experiences as immigrants and subjects of the empire, Indians do not empathise with black communities.

What can measure the extent of Indians’ anti-black feelings than the society’s obsession with fair skin? No one is ignorant of the huge market of fairness creams that promised to give a lighter skin shade to their customers. As ridiculous as those ads were, people were buying them as they bought into the stereotype that fairer skin is ‘superior.’

The idea of light-skin superiority is a product of colonialism. The British colonialists discriminated against Indians based on their skin colour. That discriminatory culture has been carried down as we see North Indians target people from Southern India for their skin colour.

Further, skin colour has also become a standard for choosing brides. As a woman myself, I can attest that these beauty standards have influenced most Indian girls, who have either wished for fairer skin or have found comfort in their fair skin. A darker skin tone has also affected one’s confidence and made them feel undesirable.

Nair’s film portrays these home biases, which have also found a place in the immigrant communities of the United States. The protagonist, Mina, while talking to her mother regarding a marriage prospect, jokes about the anti-black stereotype at the beginning of the film:

You got a darkie daughter. Harry’s mother don’t like darkies

We soon find out that the comment was no joke. Throughout the film, we see that Mina is often criticised for her beautiful, dusky skin. She finds herself not passing the qualifications of ‘marriage material.’

You can be dark and have money, or you can be fair and have no money, but you can’t be dark and have no money and expect to get Harry Patel.”

It is not be surprising that these biases translate to explicit racism against the African American communities because of their skin colour. A ‘no-black marriage’ rule, accompanied by various slurs for black people, remains typical of immigrant Indian households. It shows how Indians have adapted to racism in the West and have chosen to place themselves in the racial hierarchy rather than standing in solidarity with African Americans.

Denzel Washington, as charming and sensitive as he is, still gets referred to in the movie as a “carpet cleaning kaalu” a common slur used at the desi households. The derogatory term relates directly to the skin colour; when called out, it invokes rebuttal — ‘if they’re black, aren’t they Kala?

Indians have conveniently accepted their position in a hierarchy — below the whites, above the blacks. “Can you imagine dumping Harry Patel for a Black?” It is the kind of dialogue that any aunty would gossip about if they found out about an interracial relationship between an Indian woman and a black man.

Nair’s movie also shows how the Black community has acknowledged the differences. Demetrius, played by Washington, faces a serious backlash against his relationship with Mina. His brother often had people coming up to him to complain about Dimitrius’s attitude, which had changed since “your brother thought he got himself a white chick.”

Mississippi Masala brings forth experiences that the gaps between the two communities of America are indifferent to. Upon meeting Demetrius’ family, Mina tells them she has never been to India. Demetrius’ brother relates to it right away. He immediately makes her one of them; “you’re just like us. We are from Africa, but we have never been there either.” The second and third-generation Indian immigrants only knew the United States as their home. Yet, their roots are Indian: “mix masala,” as Mina calls them.

In addition to discrimination based on skin colour, Indians share many parallels with racism. When slavery came to an end, Indians were beginning to replace the Africans in a new system: indentured labour. The British colonialists transported Indians to many parts of the world to work on sugarcane and cotton plantations or to build railroads. Mina’s grandfather was taken to Uganda in the same way.

Mina’s father was born on Ugandan soil and made it his home; in the same way, Mina had made the United States her home because they were forced to flee Uganda because of Idi Amin. After the 1970s, the United States and the UK saw an influx of Indian refugees fleeing from persecution in Uganda, and many remained behind, settling to start a new life.

If these experiences aren’t enough to evoke fraternity between two communities, the American experiences also have more for them to relate to. Indians, like African Americans, face discrimination from the white majority. While there is no comparison of experiences, Mina finds comfort in Demetrius’ company because they could easily discuss such issues.

Mina: “You know how many people come to our motel, and they look at us and say, not another goddamn Indian.”

Demetrius: “Well, Miss Masala, racism or as they now say ‘tradition’ gets passed down like recipes.”

Despite these similarities, the otherness of blacks along with the hierarchy has been maintained as the immigrant communities have tightly held on to anti-black beliefs.

Children of Immigrants have begun calling out racism and the anti-black practices within their community. It is slowly starting to be recognised as a problematic ideology Nair portrayed in Mississippi Masala 30 years ago. So, the question still remains: Will the movie remain relevant 30 years from now?

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]