At the end of Mahatma Gandhi Road, in the city of Bangalore, stands a black-stoned statue of a visionary. With a smile on his face and a hand on top of a thick book mounted on a stool next to him is a man named Ferdinand Kittel, a German Missionary, commemorated for his immense contributions to the Kannada language.

Born on April 7, 1832, in Reserterhafe, Germany, Kittel came from a family with a strong religious background as his father was a priest. At the age of 17, he discontinued his education to explore his spiritual learning and upon his father’s wish, he joined the Basel Mission and arrived in India at the age of 21 in 1853.

Kittel had a strong grasp of languages from a young age. He had already mastered Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French, and English, and during his stay, he studied Kannada, came to love it, and contributed greatly to its development.

He travelled all over Karnataka for over two decades and undertook exhaustive studies of the language, music, and culture. A famous Kannada poet, D R Bendre, described Ferdinand Kittel as the man who strived to mirror Kannada to Kannadigas. ‘What made him different from other missionaries is that he spent a lot of time among the local people understanding their culture and way of life,’ says historian S Settar.

In 1862, he began writing on religion, Kannada poetry, grammar, dictionary, and school books. He published Kathamala, narrating the life of Jesus in Kannada poetic metric, as he strongly believed that preaching Christianity was much more efficient when done through songs and music, especially in the native language.

In 1872, Kittel edited Shabdamani Darpana of Keshiraja and, in 1875, Chandombudhi of Nagavarma. Kittel also wrote articles for Mangalore Samachara, the first Kannada newspaper started by Rev. Hermann Friedrich Mögling, a fellow German.

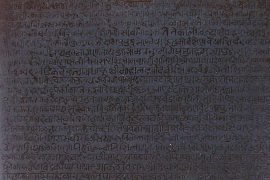

He is most famous for his Kittle Nighantu, Kannada-English dictionary, and the Kannada Grammar. Completed in 1894, the Kannada-English dictionary consisted of 70,000 words on 1,752 pages.

Kittel relied on the elite and literary works and covered proverbs and colloquial verbiage. According to Kannada literary sources, the dictionary is not limited to giving the meaning of words; it is a self-teaching book, full of literary allusions, that also works as a thesaurus. The dictionary is considered unparalleled in any Indian language.

‘It is an important work in the Kannada language, unsurpassed till date,’ says Settar, who owns an original copy of Kittel’s labour of love. He also pointed out that the quality of the paper and the leather binding are far superior to the quality of current commercial copies, which do not stand the test of time.

In 1860, Kittel married Pauline Eyth, a school teacher in Vaihingen, Germany. Eyth died giving birth. In 1866, Kittel returned to Germany with his sons, married Julie Eyth, Pauline Eyth’s younger sister, and returned to India in 1868. He worked until his second return to Germany in 1877.

Kittel’s keen interest in the language and his focus as a lexicographer on missionary activities earned him criticism from the Basel Mission. However, his commitment to the compilation of the dictionary compelled the committee of Basel to permit Kittel to return in 1884 and spend most of his time on the dictionary. He returned to Europe due to troubles with his eyesight and continuous headaches in 1892 and continued to work in Tübingen, Germany.

Kittle Nighantu took 24 years to complete.

Kittel’s magnum opus paved the way for the development of many works such as ‘A Grammar of the Kannada Language: Comprising the Three Dialects of the Language,’ books on religions, translations of poems and carols, textbooks, and other significant editions.

While Kittle is posthumously celebrated in Southern India for his contribution to the development of language and culture, he is forgotten in Germany after he passed away on December 18, 1903, in Tübingen, Germany. Though his work was known worldwide, and despite being conferred with a doctorate by the Tuebingen University of Germany, he was considered to be an ‘outsider‘ when he was alive.

Around 1988, the Austin town of Bangalore was renamed Kittle Nagar, and his statues in Bangalore and Dharwad mark his legacy in India. Kittle, who came to preach gospels to the natives of South Indians, may have been an outsider in Germany but remains celebrated as an Indian among the Indians.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]