The freaky genius of Bhagwat Chandrasekhar, interspersed with the shining abilities of Anil ‘Perfect-10’ Kumble, the classical legerdemain of Shane Warne, the ‘Wizard of Oz’ etc., have done a world of good to leg-spin bowling — the game’s most demanding, and difficult, road of specialisation.

For one lucid reason. The internal chemistry of leg-spin bowling is a verse, beautified by song, where only a select few reach a state of buoyancy and wish-fulfilment. Leg-spin bowling is an art that cannot, like any creative pursuit, be forced on the unwilling mind. Its elements of instructions should be presented to the mind always in childhood, as a sort of amusement for the natural bent of acquisition: for the difficult trade to develop, and, thereafter, attain its fruition.

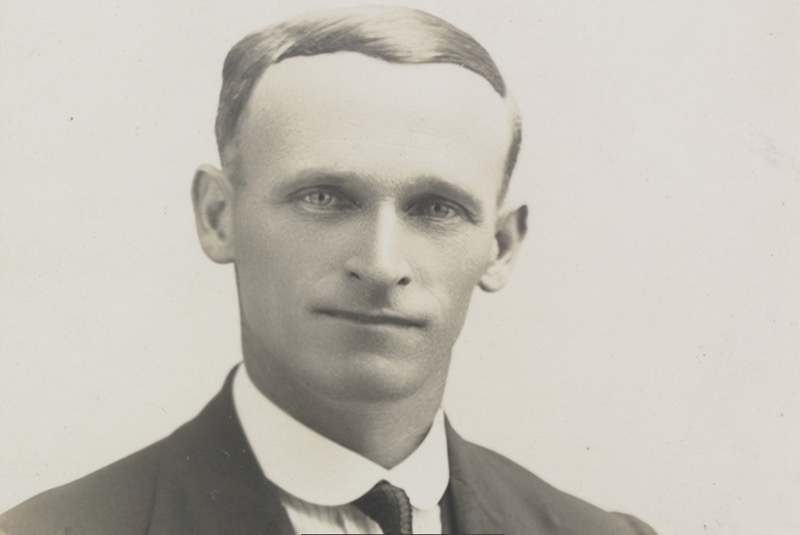

All great leg-spinners, through history, have been outstanding paradigms of such an upbringing. But, none comes close to fit the description better than Clarrie Grimmett, whose expanded human abilities for leg-spin bowling moved far beyond the confines of any physical evolution theory. Grimmett’s leg-spin was a revolutionary development — an almost out-of-body (OBE) experience.

If creativity was a basic factor in Grimmett’s psyche, his artistic cogence always bid fair to cognition: a facility, which created a dynamic energy field for his sublime art to sprout forth without external manipulation.

Cricket Boffin

Grimmett was, doubtless, cricket’s first researcher. He had immense cricketing talent, pure love, and an endless obsession for the game. He was truly a genius with an infinite capacity for taking pains. So much so, Plato’s assertion that too much of sporting indulgence was dangerous did not apply to Grimmett’s experiential fervour and aptitude. Grimmett researched incessantly and assiduously. He, thus, earned for himself a lofty seat among the game’s mighty for all time to come.

It was paradoxical that Grimmett, as a schoolboy, had nursed the idea of becoming a fast bowler, what with his frail frame. But, destiny was manifest when an island teacher, in New Zealand, decided that the young lad’s fortunes lay elsewhere — as a spinner. It did not take long, thereafter, for Grimmett to concentrate on leg-spin, his own frontier and monitor, and think it all out constantly without ever reaching any degree of boredom.

Grimmett’s scope, or his ‘assay’ into the game, was astounding. He had a theory for everything. His approach to bowling his ‘express’ variety was hurried — and, he often completed his over within two minutes. He’d, then, be ready for his next with animated expectation and the will to succeed — an objective lesson for today’s aspiring, and established, leg-spinners.

Grimmett’s migration to Australia was what the Creator had ordered for him. There he was, experimenting something new, at every step. But, his nature of practice was not aimless. As Jack Fingleton wrote, “Grimmett lived to perfect something new in his bowling art. He was forever experimenting, his wrist, his body, at this and that angle at the moment of delivery, his shoulder at varying heights. One particular delivery he produced took him some 12 years to perfect before he would bowl it in a big game. This was known as the ‘flipper,’ because of the click of his fingers when he released the ball. He bowled it with a leg-break action and the ball, making pace from the pitch, would come in from the off.”

Inventor Beyond Compare

Grimmett’s bowling action was picturesque — a little hop, and skip, at the beginning, and as he jogged a few steps his right arm took its little swing back. Many a batsman could read his flipper, thanks to the clicking of Grimmett’s fingers. But, Grimmett would not be perturbed at all. He revelled in playing the waiting game. At the right moment, he would ‘hold’ one back, and make the ball turn from leg: a harmless, but well-disguised, leg-break. The batsman would be flummoxed, as it were.

Grimmett never fancied bowling at the nets. He did not want distractions. The control of length, or direction, was of paramount importance to him. Grimmett built his own pitch in his back garden in Melbourne. He practiced in his ‘laboratory’ at every possible opportunity; his sole friend, to retrieve the ball, being a fox terrier.

Grimmett researched with all types of balls: red cherry, tennis, and even ping-pong. For his spinning thesis. His dissertation: most spinning deliveries, which did not fizz off the pitch, were fume; what was ideal was speed derived off the wicket. As he learned to swerve the ball, with his own kind of spin imparted to it, complemented by the arm movement which had a real bearing on the flight of the ball, Grimmett’s sublime art attained its nirvana: invincible length and direction. The outcome? The batsman’s feet twittered at the prospect of playing Grimmett’s first delivery.

The ‘Sly Fox’

Grimmett made his Test debut, for Australia, against England, in 1924-25. In his first outing, the ‘sly fox’ as he was wryly referred to, took 11 wickets, from 31 overs, for just 82 runs, in the match. Soon enough, and in harness with the great Arthur Mailey, Grimmett performed creditably during Australia’s tour of England, the West Indies, and South Africa. His best was yet to come. During Australia’s tour of South Africa, in 1935-36, Grimmett took 44 Test wickets, at an incredible average of 14.59.

The real feather in Grimmett’s cap was achieved in England, in 1934-35. It was leg-spin bowling at its acme: a revolution brought about by the master in association with his ‘protégé,’ Bill O’Reilly. The tweaking duo picked up 55 of the 73 English wickets that fell in Tests that summer, and emerged as the greatest leg-spin combine in Test history. This was not all. During the course of their English sojourn, Grimmett and O’Reilly went on to collect over a hundred wickets apiece. Yet, Grimmett was soon a forgotten man, a victim of selectorial solecism, what with age too not being on his side.

Grimmett took his batting seriously: a constant source of pride. And, he was a great fielder too. Wrote O’Reilly, “He (Grimmett) knew all there was to know about fielding in the covers, a position where he shone without any show of flamboyance. Never once did I see him dive headlong at a cover drive: there was no need for him to do so; he always seemed to have sufficient time to the ball on two feet and take it in two hands.”

Picture this. Grimmett had such batsmen, like Walter Hammond, the king of the cover drive, and one of the greatest batsmen that ever held the bat in hand, to contend with. That he often emerged trumps with the ball speaks a fascinating language — all by itself.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]