On September 5, 1379, in a quiet, cloistered French monastery, something extraordinary—and rather absurd by today’s standards—occurred. Two herds of pigs, typically seen as humble creatures of the farm, suddenly became the focus of one of the most bizarre judicial proceedings of the medieval period.

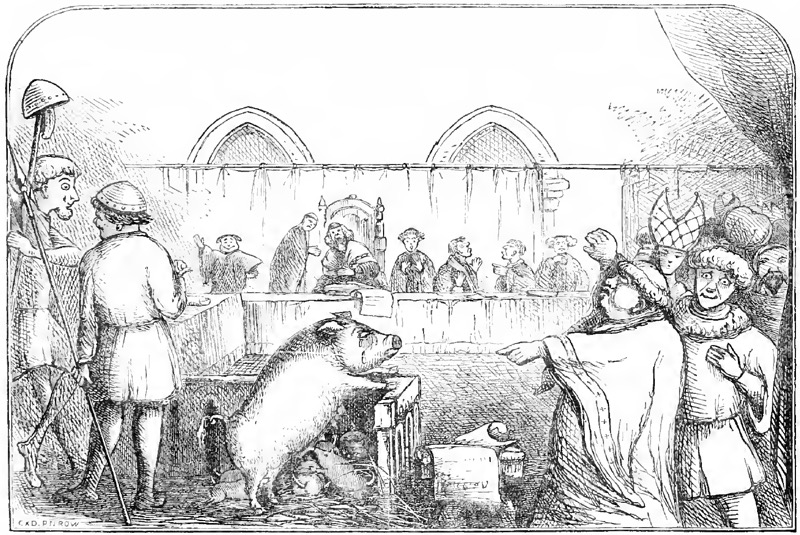

The pigs grew agitated, trampled an unfortunate man named Perrinot Muet, and killed him. In an act that would seem more at home in a dark comedy than a courtroom drama, the animals were tried, found guilty of murder, and sentenced to death. This strange episode is not a singular anomaly in the history of justice; it is a manifestation of a broader, more common medieval practice: animals, like humans, were once tried, convicted, and punished under the law.

The notion of applying legal principles to animals is at once perplexing and perhaps humorous in modern society. However, it is critical to understand that, in the Middle Ages, the legal system was far from the rational, human-centred enterprise it is today.

The maxim ignorantia juris non excusat—“ignorance of the law is no excuse”—holds that the law assumes individuals are aware of its dictates, and therefore cannot claim ignorance as a defence. Today, this principle applies exclusively to humans. But in centuries past, animals, as well as humans, could be held accountable under this legal doctrine; it was a widespread and accepted practice in Europe and the British Isles during the medieval period.

The origins of this tradition can be traced back to ancient law codes. The Hebrew Bible, for instance, prescribed the death penalty for an ox that gored a man to death. The rationale was that the animal, as a potential threat to human life, had to be dealt with in accordance with society’s laws.

Likewise, in classical Greece, the philosopher Plato posited that if an animal killed a human, except in cases of sanctioned combat, the victim’s family had the right to prosecute the animal. These early legal precedents laid the groundwork for medieval jurisprudence, in which the rights of humans and, by extension, the obligations of animals were formally recognised in the eyes of the law.

By the Middle Ages, this concept had morphed into a full-fledged judicial practice. Animals were not only held accountable for their actions but were also subjected to formal legal proceedings. These trials were remarkably detailed, with investigations that mirrored those of human criminal trials.

In some cases, animals were provided with defence attorneys, and, if insufficient evidence was presented, the charges might be dropped, resulting in an acquittal. A French pig that killed a child in Caen was once described by the courts as having committed an act so contrary to its “natural” role as a domestic animal that it was viewed as a criminal capable of moral judgment. In this sense, medieval courts operated on a curious understanding of animals as moral agents, beings capable of understanding and violating human social norms.

As peculiar as these proceedings may seem, they were grounded in a belief that animals, particularly domesticated ones, possessed the same moral compass as humans. The assumption was that since animals lived in proximity to humans, they should be expected to adhere to the same ethical standards that governed human behaviour.

This view was rooted in religious and philosophical traditions. For example, French legal scholars in the sixteenth century argued that animals should be held accountable for their actions because they were capable of understanding man-made laws. Under this worldview, animals, though non-human, were expected to uphold the social contract with humans; if they failed to do so, they would face punishment.

This judicial approach to animals was not confined to pigs and cows. In 1546, the French Parliament, the highest court in the land, ruled that a cow that had killed a man should be hanged and then burned at the stake. The execution of animals was seen as a way to demonstrate the seriousness of crime, a sort of divine retribution to ensure that justice was meted out—even when the defendant had hooves or paws.

There were also cases where animals were tried for less violent offences. A he-goat in a Russian village, for example, was banished to Siberia for butting an important official while the official was fastening his shoes. The punishment might seem comical, but it was indicative of a worldview that expected animals to conform to societal norms.

Punishments for animals varied widely, from a few weeks of imprisonment to execution by hanging, burning, or even drowning. While it is difficult to imagine a pig or a goat sharing a cell with human criminals, that was indeed the case. Animals convicted of crimes were often thrown into jails alongside their human counterparts, awaiting their fate.

Yet this approach also had its inconsistencies. It was not always the animal itself that bore the full brunt of responsibility. In some instances, the animal’s owner was held partially accountable for the animal’s actions, especially if the animal had been improperly cared for or had been acting under the direction of the owner. This created a legal relationship of sorts between the animal and its owner, in which the owner was seen as the employer and the animal as the employee, both bound by the law.

The reach of animal trials extended beyond the more conventional domesticated animals. Insects, too, were subjected to legal scrutiny. Swarms of locusts or colonies of rats, particularly when deemed responsible for damaging crops or other property, could be excommunicated by the clergy, a practice that combined secular and religious authority.

The Church, which held immense power during this period, played a central role in these proceedings. In some cases, formal provisions were even made for sanctuary, where animals, particularly pests, could claim a designated plot of land to prevent further harm to human property. These practices were seen as rational expressions of a world in which human and animal lives were inextricably linked through laws that governed both.

The medieval legal system’s treatment of animals is particularly curious because it assumed that animals, like humans, were capable of distinguishing right from wrong. This idea was rooted in religious doctrines that saw the world as a hierarchical system in which animals, as God’s creations, had a duty to abide by the moral and legal standards set by humanity.

Today, this notion seems far removed from our understanding of animal rights and ethics. The modern movement for animal rights is grounded in the belief that animals, though deserving of protection, are not capable of moral agency in the same way as humans. In fact, had animals been tried as they were in the Middle Ages today, it would be considered a violation of their rights and a profound injustice.

While our legal systems now emphasise the innocence of animals—recognising that they do not commit murder or homicide intentionally—the medieval trials speak to a different era’s attempt to reconcile the natural world with the structures of law. In a strange way, these trials reflect humanity’s evolving understanding of animals, from being viewed as moral agents to being recognised as beings deserving of protection and consideration, even if they cannot be held responsible for their actions in the same way humans are.

In recognising the inherent innocence of animals, modern society has perhaps advanced in a way that mirrors the very concept of justice medieval people were trying, albeit in an absurd fashion, to achieve. The bizarre nature of animal trials in the past provides a curious window into the history of our understanding of the law and its boundaries—boundaries that, fortunately, we have come to realise must be more compassionate and less punitive, particularly when it comes to creatures incapable of choosing their actions.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]