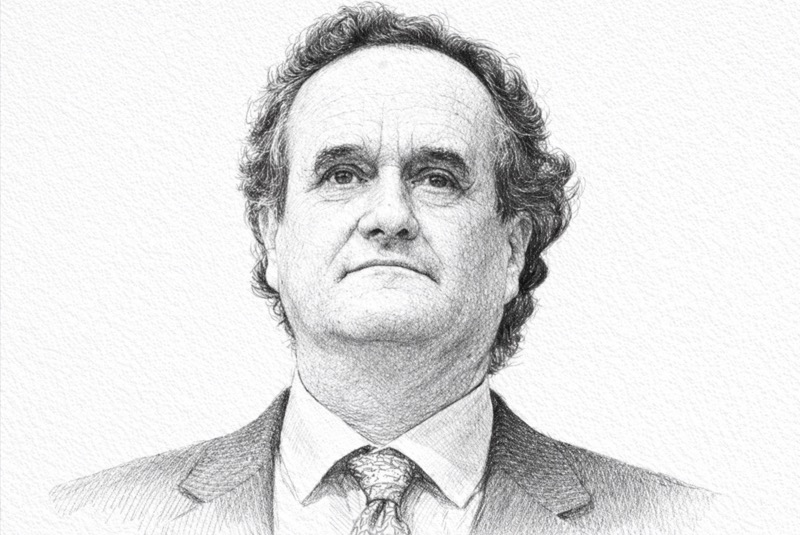

Of the countless voices that have echoed across the Indian subcontinent, few were as unexpected as that of Sir Mark Tully, the BBC correspondent whose gentle, measured tones became synonymous with pivotal moments in modern South Asian history. Long before the internet, before rolling news channels, and well before podcasts gave rise to a new generation of narrative storytellers, Tully’s broadcasts carried across dusty villages and teeming cities alike; they were sometimes re-aired in Hindi, Urdu, Tamil, Nepali and Bengali, so that even those with no access to English could hear his calm narration of events that shaped their lives and futures.

In a crowded room of foreign correspondents, his voice was distinctive not just for its clarity but for its warmth. Colleagues often remarked that Tully didn’t sound like someone reporting on India—he sounded as if he were reporting from within it, a feat underscored by the fact that he achieved a rare level of fluency in Hindi and embraced the country’s rhythms with a curiosity that transcended professional obligation.

This fluency was no mere linguistic parlour trick; it was emblematic of a deeper human engagement that set him apart at a time when many foreign correspondents remained perched in diplomatic hotels, peering at India from a distance. Instead, Tully wandered its streets, shared its chaats and chai with locals, and learned to think—and sometimes to dream—in its idioms as much as its language.

That he came to India twice in his life—first as a child in Calcutta (now Kolkata), born there in 1935 to British parents, and later as a professional journalist—imbued his story with a symmetry that defined his relationship with the land and its people. Sent to England for schooling at Marlborough College and Trinity Hall, Cambridge, he studied history and theology, even spent a short spell in a seminary pondering the priesthood—a period he later described as too constrained for a person with both a restless spirit and a fondness for worldly pleasures. This unlikely combination of spiritual curiosity and worldly delight—equally at ease in discussions of Sufi saints and dusty railway platforms—would become a hallmark of his work and his prose.

Tully joined the BBC in 1964. By 1965, he was posted as an administrator in New Delhi, the city that would become his home for more than half a century. It was only a matter of time before he found himself behind the microphone—his first broadcast, by his own recollection, reporting on a vintage car rally where a maharaja offered champagne at a picnic table—and thus began the career of a man whose instinct for the telling detail would enthral listeners across continents. Soon, he was appointed India correspondent and then bureau chief for South Asia, a role he held for over two decades, shaping the BBC’s coverage of a region undergoing dramatic change.

From the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, which led to the birth of a new nation, to the fraught years of the Emergency (1975–77) under Indira Gandhi, Tully’s voice was there, guiding listeners through complex political landscapes with a rare blend of clarity and empathy. He covered Operation Blue Star at the Golden Temple, the tragic assassinations of Indira and later Rajiv Gandhi, and the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, when a hostile mob even chanted “Death to Mark Tully” at him before local allies sheltered him—moments that reminded him and the world that journalism’s frontiers are not merely geographic but human.

Yet it was not only the crisis points that defined his legacy. Tully’s reporting brought attention to the subtle currents of social change in India: the syncretic festivals danced in small towns; the long waiting lines at dusty railway stations; the everyday negotiations of caste, faith, and aspiration that elude neat headlines but reveal the soul of a country. His extraordinary range, from political upheavals to cultural vignettes, made him not just a chronicler of events but a weaver of narratives that felt lived and immediate.

His fluency in Hindi was emblematic of this immersion. He once insisted that locals address him in Hindi, growing visibly annoyed if people defaulted to English, a testament to how deeply he identified with the linguistic textures of the land he reported on. And yet, such engagement was not mere mimicry; it was rooted in a genuine respect for what language carries: not just words but worldviews, histories, and hearts. That respect is why, despite an education in England and a life shaped by British institutions, Tully was reluctant to be labelled an “expatriate”—he famously quipped that his heart was “Indian, with a bit of English too,” a line that captured his hybrid identity with affectionate precision.

Beyond broadcasting, Tully’s literary output deepened this portrait of India. Books such as No Full Stops in India, India in Slow Motion, and The Heart of India extended his radio work into reflective essays, marrying reportage with sensibility and rendering the subcontinent’s complexities in prose that was both elegant and accessible. With his longtime partner and fellow writer Gillian Wright, he explored subjects as diverse as spiritual pluralism and rural rhythms, producing works that conveyed the nation’s rich tapestry in thought and sentiment rather than mere statistics.

Yet Tully was as human and flawed as the stories he told. Friends recalled evenings of convivial debate, whisky in hand, and conversations that ranged from cricket victories to the deepest religious paradoxes, often lasting until dawn. He once declared his love for Irish whiskey and Old Delhi street food with equal relish. Such anecdotes reveal that his passion for life matched his passion for the craft of journalism—a blend of rigour and rumination that gave his voice its unmistakable warmth.

Recognition of that distinct voice came in the form of honours from both nations that shaped his life. He was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire and later knighted in 2002 for his services to broadcasting, while India bestowed on him its Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan, rare civilian honours for a foreign-born journalist. These were not mere decorations but acknowledgements of a bridge—of trust, respect, and mutual affection—that he had built across cultures.

In his later years, Tully continued to reflect on life’s deeper questions, hosting the BBC Radio 4 programme Something Understood, where he explored spirituality and the human condition with the same generosity and introspection that marked his journalistic work. Even in retirement, his presence remained integral to the cultural conversation between nations, reminding listeners that journalism, at its best, is not detached observation but engaged, empathetic listening.

And then, on 25 January 2026, Sir Mark Tully died in New Delhi at the age of 90, closing a chapter on a life that had witnessed, interpreted, and shaped how the world understood a rapidly changing South Asia. Tributes poured in from all corners—from India’s prime minister to everyday citizens who remembered tuning into his broadcasts. His passing was marked not as the end of a foreign correspondent but as the farewell to a voice that, for millions, had become a trusted companion through decades of change and continuity.

In the memory of those who heard him, Mark Tully remains less a chronicler of history and more its living echo, a reminder that journalism’s true power lies not only in witness but in the gift of listening — deeply, generously, and without fear.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]