In February 2020, a widely publicised event, “Namaste Trump,” welcomed the US President Donald Trump on his inaugural visit to India. Before the event, Indian authorities launched a frenzied beautification drive at the Narendra Modi Cricket Stadium in Ahmedabad. They hastily erected a half-kilometre brick wall enroute to the stadium, which Trump’s motorcade was to take.

Behind the two-meter-high wall — painted green, daubed with bright golden letters—lay a world of grey and despair, the Sarania Vass slum that housed more than 800 families. The wall stands as an emblem of a new India under Narendra Modi, one that conceals the real India, teeming with millions of poor and neglected people.

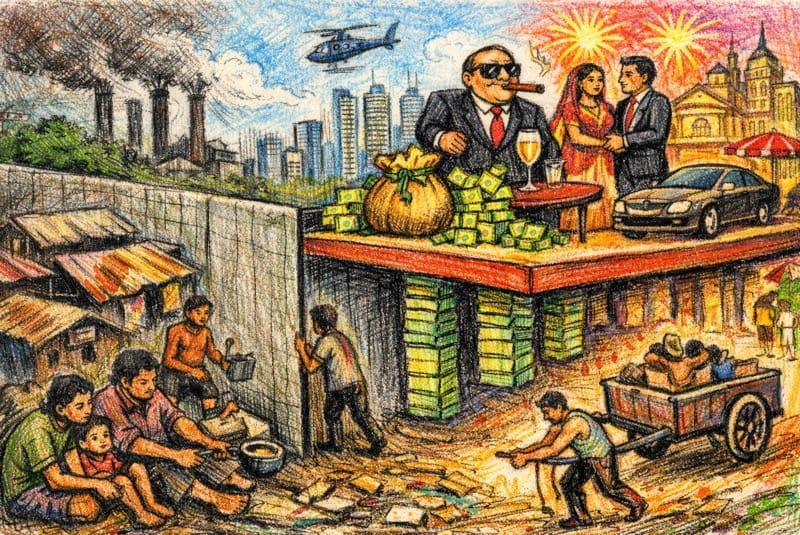

The barrier also serves as a striking visual metaphor for “The Tale of Two Indias”—the India for the rich and the India for the poor. It is an India in which the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, reconciling themselves to their fate as their lives grow more miserable.

Ostentatious displays of wealth are juxtaposed with the grim realities of those who live on the margins. Indeed, the paradoxes of skewed development are stark in modern India. For instance, adjoining “Antilia,” the second most expensive home in the world, belonging to India’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, lies the Golibar slum. While Mukesh Ambani rolls around in his fleet of Rolls-Royces, the residents of the slums live in overcrowded shanty houses, bereft of proper sanitation and basic amenities such as clean drinking water, toilets, and drainage; the inhabitants face a barrage of forceful evictions and controversial slum rehabilitation programs.

The lavish pre-wedding gala for Mukesh Ambani’s son, which cost upwards of $150 million, was attended by a glittering array of global celebrities. This global media event was televised and livestreamed as “India’s soft power moment” and marketed as a cultural renaissance and revitalisation of authentic Indian traditions.

The global “who’s who” was ushered in by the quintessential display of Indian hospitality embodied in “Athithi Devo Bhava” (Guest is God). It explicitly offered a visual contrast between unimaginable luxury and visible deprivation. The street vendors were removed from surrounding areas ostensibly “for security reasons”; public roads were closed; police diverted to the venue; cities sanitised for optics.

While revelry and merriment reached a crescendo, an unseen, unheard India continued its silent ordeal. As millions of dollars were spent on dazzling flower arrangements for the wedding, slums in Mumbai were deprived of basic needs; while bottles of champagne flowed, hordes of hungry children slept on pavements. India is rising and shining, but only for the few. Elitism is being self-perpetuated into “Hereditary Meritocracy,” permeating all walks of life.

In Modi’s so-called “Amrit Kaal,” an era touted as an “auspicious time,” the chasm dividing the rich and the poor is expanding at an accelerated pace. Yet poverty is made invisible, and economic deprivation is skillfully cloaked in dubious statistics and data.

Concerns over the reliability of India’s economic data have drawn international scrutiny. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has raised significant reservations about the integrity of the country’s economic statistics, particularly regarding the estimation of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). As a result, the IMF downgraded India’s GDP estimation process to a “C” grade, signalling deficiencies in data quality and methodology.

The Modi government often criticises Nehru’s economic policies and blames him for India’s economic ills. This diversionary tactic, ubiquitous in today’s political debates and campaigns, shifts attention from current policy failures by invoking historical references. Avoiding shared responsibility and accountability is characteristic of the NDA’s approach to governance.

Modi’s era, since 2014, is defined by deepening socioeconomic inequalities. After 10 years in office, it has reached levels reminiscent of the British Raj. In 2024, according to the World Inequality Database (WID), the top 10 per cent of earners in India accounted for 58 per cent of total national income. In contrast, the bottom 50 per cent share an abysmal 15 per cent.

A counterargument is the recent World Bank report on inequality, which uses data from 2022-23 surveys and positions India as the fourth-most-equal country globally, with a Gini Coefficient of 25.5. This is a statistical illusion rather than an economic reality. The Gini Coefficient cited by the World Bank measures only consumption inequality, not income or wealth disparities. When examining income and wealth inequality, India’s coefficients are 0.62 and 0.75, indicating rampant inequality. For India’s poor, consumption equals income, leaving no savings or wealth creation.

An appalling trend is the administration’s overt patronisation of the ultra-rich, especially the two behemoth corporations Adani Group and Reliance Ltd, led by Gautam Adani and Mukesh Ambani. These conglomerates are promoted as ‘national champions’ similar to Japan’s Zaibatsu and South Korea’s Chaebol, to buttress policy goals.

However, they operate mainly in non-tradeable infrastructure sectors, targeting the domestic market, insulated from global competition by protectionist policies. This forfeits India’s opportunity to build new global brands beyond Adani Group, Reliance, and a few longstanding companies. Critics refer to India’s economy as the “Ambani Adani (AA) economy” due to the government’s overt patronage of these giant business houses.

There is ample evidence that Prime Minister Modi favours the businessman Gautam Adani. It is an “open secret,” a clear example of nepotism. The businessman backed Modi when other Indian business leaders and the international community ostracised him for the Gujarat communal riots in 2002 that culminated in the pogrom of more than two thousand Muslims. In the next decade, Adani’s loyalty was rewarded; his company bagged multiple government contracts, helping it gain a monopoly in oil and gas exploration, coal trading, mining, power, and infrastructure.

When Modi became prime minister, the government’s approach shifted. In 2018-19, six airports were privatised, and all contracts were awarded to the Adani Group, even though it had no prior experience in airport management. Adani’s Godda power plant was designated as a Special Economic Zone—the first such status for a standalone power project in India—granting significant financial benefits, including $60 million in exemptions.

The Mundra Port, owned by Adani, faced accusations of environmental violations. However, a 200-crore ($34 million) fine imposed in 2013 by the previous Congress government was reversed in 2015-16, when Modi took charge, clearing the company of any wrongdoing.

The Modi government created new rules favouring Adani when the Supreme Court cancelled coal block allocations to retain mining rights for a large coal block. A similar rewriting of policy occurred when Ambani’s telecommunications behemoth, Reliance Jio, was accused of predatory pricing; the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) hastily amended the rules.

Adani’s international expansion was closely linked to Modi’s diplomatic visits, which helped the group enter countries like Israel, Malaysia, Vietnam, Tanzania, and Bangladesh. After the Hindenburg Report accused Adani Group of brazen stock manipulation and accounting fraud, the company called it “a calculated attack on India.” Nationalist rhetoric is often invoked to deflect criticism of the BJP-affiliated businesses; terms like “anti-nationals” and “Urban Naxals” are frequently employed in political discourses, amplified by government-aligned media houses.

The concentration of wealth in India is alarming; all economic gains since 2014 have been monopolised and appropriated by the top 1 per cent. To put things into perspective, the top 1 per cent owns almost 40 per cent of national wealth, the top 0.1 per cent controls 22 per cent and 0.001 per cent has appropriated 16 per cent of India’s wealth.

Modi’s promise of equitable growth and broad-based development was a sham; India ranks as one of the most unequal societies on the planet, only behind South Africa and Brazil. In a country of 1.5 billion people, the fact that a mere 15,000 people own 16 per cent of its wealth is a testimony to the egregious failure of promises of inclusive growth; the deeply entrenched oligarchy could deteriorate into a plutocracy in the future. Since 2014, the Indian economy has taken a disastrous turn towards ‘Megacorporate Capitalism.’

This inequality in income and wealth distribution has come at the expense of the middle class’s economic fortunes. In 1991, the middle 40 per cent had a 40.7 per cent share of national wealth. However, by 2023, it had declined sharply to 29 per cent.

An administration that boasts of a growing number of billionaires (358 in the last year) has truly become a “Billionaire Raj,” making India the third-largest hub, only behind the United States and China. If creating billionaires is touted as an economic achievement, it must also be juxtaposed with the fact that 800 million Indians have no choice but to rely on free or subsidised food programs due to diminished economic prospects. This distribution scheme maximises political visibility, not productivity. It sustains consumption rather than building human capital or transforming livelihoods.

Socioeconomic inequality is exacerbated by underemployment and unemployment, especially youth unemployment. A 2024 International Labour Organisation (ILO) report sent shockwaves through the developing world when it found that 83 per cent of the youth (aged 15-24) in India are unemployed.

India objected to the ILO findings and cited official Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data estimating the youth unemployment rate at a meagre 10.2 per cent. In contrast, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Industries (CMIE) reported an alarmingly high 45.4 per cent in 2022-’23.

Several eminent Indian economists have expressed grave misgivings about the government’s neglect of the unorganised sector. This omission has a contagion effect on prevailing socioeconomic inequalities in India, which is more structural than cyclical, caused by a lack of political will.

A question raised in the Rajya Sabha in 2017 received a response: the informal economy accounts for 94 per cent, and only 6 per cent are employed in the organised sector. Informal economy accounts for more than 45 per cent of GDP, and 60 per cent of all consumer expenditure transactions remain cash-based. When the government releases growth data confirming a stable 6.5 per cent GDP growth rate, it essentially captures growth in the organised sector.

Quarterly data from the unorganised sector is delayed. If its growth matched that of the organised sector, youth and overall unemployment rates might have dropped significantly. Using proxies and benchmarks to estimate its growth assumes it’s unaffected by shocks like demonetization (2016), GST (2017), the NBFC crisis (2018), and the Covid pandemic (2020-21).

Notably, despite all macro and microeconomic factors declining during demonetisation, official GDP growth was estimated at 7.2 per cent, later revised to an improbable 8.2 per cent. It doesn’t require a PhD in economics to ascertain the fallacy of such unrealistic numbers.

The unorganised sector is excluded chiefly from input tax credit (ITC) against GST, leading to a cascading effect. Consequently, the unorganised sector is challenged with a cash flow crunch, reluctance of the organised sector to enlist them as supply chain partners, and loss of competitiveness vis-à-vis the organised sector due to expensive final products. This sector is still plagued by significant distress, which belies the government’s GDP figures of stable 6.5 per cent growth. India’s GDP figures reflect growth in capital-intensive, technology-driven industries that are less labour-intensive.

The MSME (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises) sector — which accounts for 30.1 per cent of India’s GDP, 35.4 per cent of manufacturing, and 45.73 per cent of exports — is in doldrums. Micro enterprises dominate, accounting for 60 million units and 97 per cent of informal sector jobs. However, they struggle to access affordable working capital loans from banks, often turning to money lenders instead. Given the existing set of banking laws, there is no near-term reprieve on the horizon.

Gender inequality remains a deeply entrenched issue in India, as evidenced by the country’s persistently low Female Labour Force Participation Rate (FLFP). At 35.3 per cent, India’s FLFP is significantly lower than the global average of 51.13 per cent. This figure places India as an outlier, especially when compared to other developing regions. For instance, most developing economies in Asia, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa exhibit much higher FLFP rates, generally around 56.78 per cent. Even within Asia & South East Asia, countries like Burma have an FLFP at 40.95 per cent, while Vietnam records 69.13 per cent, and Cambodia reaches as high as 73.96 per cent.

This is not just an economic issue, but impacts entire communities, deepening poverty, hindering social mobility and transferring the malady into successive generations. One of the most troubling consequences of low female participation in the workforce is its complex connection to child malnutrition. India faces some of the gravest statistics globally in this regard: the stunting rate (low height for age) stands at 35.7 per cent, the wasting rate (low weight for height) is 18.7 per cent — the highest in the world — and 32.1 per cent of children are classified as underweight.

Furthermore, nutritional deficiencies are widespread among both children and women. Approximately 67 per centof children aged 6 to 59 months, and 68.4 per cent of women, between 15 and 49, are anaemic. These deficiencies are symptomatic of deeper issues related to poverty, inadequate dietary intake, and limited access to healthcare.

India’s standing in the Global Hunger Index has only worsened over time. Since 2014, India’s rank has steadily declined, and in the 2025 report, it was placed at 102 out of 125 countries. How can a nation that boasts around 7 per cent economic growth struggle to provide sufficient food for its people? The answer lies in the interplay of declining incomes, stagnant wages, and reduced consumption, which collectively diminish the population’s ability to afford adequate nutrition.

Socioeconomic inequality in India is inseparable from social hierarchy. Caste, gender, religion and region continue to influence access to education, employment and financial credit and are integral factors in social organisation and wielding political power.

India today is a rising global economy, aspiring to become a global superpower, yet mired in a historic contradiction of locally collapsing livelihoods. The gnawing inequality raises profound ethical, moral and existential questions. Ultimately, for whom is India growing fast?

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]