In Ballari District Hospital in Karnataka, doctors found themselves in a strange battle— not against disease, but against the moon. Several pregnant women, in active labour, refused to give birth during a lunar eclipse. The medical staff watched, helpless and anxious, as tradition overruled treatment.

When oxygen levels began to dip dangerously, doctors stepped in, overriding the patients’ refusal with urgent care. This was not a rural clinic untouched by modernity. This was a government hospital in a country that launches rockets into space.

The incident, though jarring, was not unique. Across India, superstition continues to stretch into the most unlikely spaces—operating rooms, parliamentary chambers, and university lecture halls. Advances in medicine, education, and science have yet to break the grip of belief systems that predate germ theory.

Sadly, the government, far from being a force of reason, has often fanned the flames. Tradition becomes a shield. Cultural pride, a smokescreen. And science? Often sidelined.

It is easy to dismiss such events as isolated. However, they reflect a deeper national crisis in which irrational beliefs are not just personal choices, but state-endorsed practices. In Ballari, doctors had to defy not just the patients’ families, but the invisible weight of centuries. The district health officer, Dr. Ramesh Babu Y, later reminded the press that medicine must respond to physiology, not to astrology. It felt like a basic thing to say. It was anything but.

The Indian state has long struggled with this tension. Rather than confronting superstition, successive governments have often embraced it. One of the most glaring examples is the official recognition of astrology. In 2001, the University Grants Commission approved it as a university subject, not a course in cultural history but a “scientific discipline.” When critics challenged the move in court, judges dismissed the objections, pointing to astrology’s longstanding presence in Indian life. Longevity, it seems, was mistaken for legitimacy.

That decision carried a message far beyond academic circles. It told citizens that ancient beliefs could stand as scientific truth. It collapsed the boundary between knowledge and nostalgia. And it seeded doubt, not about astrology, but about science itself. When the state treats horoscopes as data, why should a patient trust an MRI?

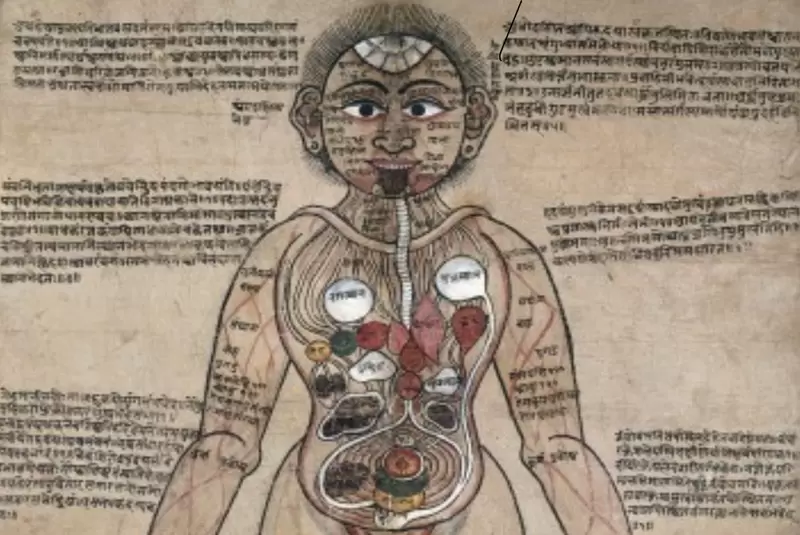

The government’s endorsement of AYUSH—Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, and Homoeopathy—presents another case. While traditional systems of medicine can offer cultural continuity and holistic care, many of their methods lack clinical validation. Still, AYUSH enjoys full ministerial status.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Modi government promoted untested immunity boosters like Giloy and homoeopathic pills. Politicians offered bizarre remedies. Cow urine was declared a cure. Amid a global health crisis, India’s public health messaging drifted into mythology.

Such policies erode confidence in scientific medicine. Worse, they divert attention from treatments that save lives. When governments elevate untested remedies, citizens lose the ability—and the need—to distinguish between verified solutions and cultural folklore. In that space of confusion, charlatans thrive, and vulnerable people suffer.

The reach of pseudoscience is not limited to health. Government buildings, including parliament chambers and courtrooms, are often designed according to Vaastu shastra, a system derived from astrological principles. Official ceremonies are held at “auspicious” hours. Even satellite launches sometimes align with planetary positions. These rituals may seem harmless. But their normalisation reinforces the idea that the stars, not science, determine success.

The state justifies these choices with appeals to “civilizational pride.” The argument goes like this: modern science is a Western construct imposed during colonialism. India’s ancient knowledge systems are not only different—they are superior. This is a tempting narrative. It offers dignity. It reclaims identity. But it also demands that myth be mistaken for fact.

There is nothing wrong with studying history. Cultural practices deserve examination, even celebration. But celebration should not mean endorsement. When ministers suggest that ancient Indians understood genetic engineering or performed plastic surgery, they do more than rewrite the past—they distort the present. These claims are not harmless. They distract from real achievements, reduce science to sentiment, and strip future generations of their ability to think critically.

The irony is hard to miss. India has one of the largest scientific communities in the world. Its engineers power Silicon Valley. Its doctors lead hospitals from London to New York. But at home, in villages and cities alike, superstition commands obedience. This dual reality—technological excellence abroad and pseudoscience at home—tears at the fabric of public trust. It confuses young minds, complicates public health, and undermines education.

The consequences, as seen in Ballari, can be deadly. Women in labour should not have to choose between the safety of their babies and the shadow of the moon. Yet many do. Across India, similar scenes play out; patients delay surgeries during eclipses, avoid medicines on “inauspicious” days, and turn to miracle cures before seeking help from trained professionals. These are not personal eccentricities. They are systemic failures.

Governments, eager to appease religious and cultural sentiment, have largely avoided confrontation. Instead of investing in science education, they cut funding. Instead of empowering doctors to speak against misinformation, they remain silent. Instead of challenging superstition, they indulge it.

Social media has only made matters worse. Platforms overflow with misinformation. Self-styled gurus and influencers peddle ancient cures and conspiracy theories to millions. Algorithms amplify them. Lies travel faster than evidence. In this environment, even the most basic scientific truths struggle to gain traction.

The solution is neither simple nor swift. But it is possible. It begins with political will. The state must draw a clear boundary between respect for culture and promotion of pseudoscience. Astrology, Vaastu, and unverified traditional medicines should not receive public funding or institutional endorsement. Instead, resources should be directed toward research, public education, and science communication.

Healthcare workers need support, both institutional and legal. When doctors push back against superstition, they should not stand alone. Public health campaigns must speak clearly and often. Natural phenomena like eclipses must be explained—not mystified. Schools must teach children how to ask questions, not simply how to repeat answers.

Ballari was not an aberration. It was a warning. It showed how deeply superstition remains embedded in everyday life. In a century defined by genomics, artificial intelligence, and space travel, lives in India are still shaped by eclipses. That is not a matter of culture. It is a matter of policy.

The Indian Constitution mandates the development of scientific temper. But a mandate means little without enforcement. If the state continues to blur the line between myth and medicine, more tragedies will follow. The eclipse will not end.

Superstition thrives when it receives official permission.

Science, on the other hand, demands courage—the courage to question, to explain, to push forward even when the answers are inconvenient. The choice is not abstract. It is urgent. And it is India’s to make.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]