Colourism, or Pigmentocracy, is a form of social capital that favours light skin over dark skin among a population within a race, ethnicity or social group. Colourism manifests itself in prejudices and partisanship in matters related to employment, marital matters, career growth, and social affinities and affects general perceptions of morality, social class and virtue.

It is a hierarchy within a hierarchy that elevates light skin to be desirable as an ontological proposition and evokes preconceived notions – however false – of the innate quality of an individual. From time immemorial, human beings have craved beauty and symmetry, spawning socio-philosophical treatises such as Aristotle’s Aesthetics and sage Bharata’s Natya Shastra, dating back to ancient Greece and India.

The perennially elusive question — ‘What is Beauty?’ — has undergone several iterations in its definition. It borders on the philosophical and metaphysical — elucidated in the writings of Plato, Aristotle and Xenofon — to its current form, centred on ‘whiteness’ and ‘fairness’ as the sole paradigm.

In Wladyslaw Tatarkiewicz’s masterpiece, ‘The History of Aesthetics,’ the Greco-Roman and ancient Egyptian ideals of beauty ascribed a divine dimension to it and often equated it with goodness. Since post-colonialism, beauty has been a Euro-centric project worldwide. This deprivation is poignantly expressed by Milan Kundera, the Czech-French novelist, who wrote:

“Beauty has long since disappeared. It has slipped beneath the surface of the noise, the noise of words, sunk deep as Atlantis. The only thing left of it is the word, whose meaning loses clarity from year to year.”

Though the concept of equating fairness to beauty is prevalent from antiquity to modern, corroborated by cultural artefacts, beauty was more cultural and heterogeneous in its scope. In the Judgement of Paris, the classical Greek story, mythological beauties Hera, Aphrodite and Athena vie for the title of the ‘fairest,’ which culminates in the Trojan War.

One of the longest-running and most successful musicals on Broadway titled ‘My Fair Lady,’ and Shakespearean Sonnet 1609 reaffirms:

From the fairest creatures we desire increase/That thereby beauty’s rose might never die.

Though colourism is a gnawing problem in many parts of the world, including Latin America, parts of Africa, South East Asia, South Asia and the United States, nowhere is it more acute than in the Indian subcontinent.

The caste system in India, expounded by the Varna classification, could be construed as a precursor to colourism in Indian society. Its historical roots warrant an astute analysis of its probable origins and subsequent establishment as the singular societal norm over millennia.

Vedas are conspicuous by the absence of any reference to colourism, except for verses depicting Dravidians in anthropological phenotypes of being dark-skinned (Krsnatvac), snub-nosed and short-statured. The Aryan migration from Eurasian steppes, who were of wheatish complexion and their stratification of Vedic society, relegated Shudras as inferior to the twice-born Brahmins, Kshatriya and Vaishya — in whose service they were entrusted to — in the social hierarchy, could have sowed the seeds of colourism in Indian society.

This was exacerbated by segregating a sizable percentage of the population as untouchables and pariahs, and along with Shudras, toiled under the tropical Sun and acquired distinctive shades of black, bronze and brown skin colours. The endemic caste system, dubitably, might have predated Muslim invasions and European colonialism in creating beauty norms and standards in Indian society.

Yet, a fair-skinned theme and size-zero figure as exclusive parameters of beauty were quite alien in ancient and mediaeval India. According to historian and archaeologist Madhur Dhavalikar, unearthed Mauryan figurines dating back to the fourth to second century BC provide glimpses into prevalent beauty standards as they represent women with large breasts, wide hips and tapering legs. Similar depictions could be seen in the works of Bhartut in the Sunga period during the 1st century BC.

However, Sanchi Stupa sculptures depict women as contorted into a S-shaped curve, which was also the dominant theme during the Kushan period from the first century AD to the fourth century AD. This representation later became a pan-Indian standard.

Goddess Parvaty, considered as the personification of beauty, is narrated as ‘slender-bodied with comely hips and a moon-like face,’ denoting the resplendent glow and occasionally depicted as having golden and yellow skin colour, another symbolism as the mother of ripened harvests.

Sangam poets of South India endowed heaps of praise for the ‘darkness of full black tresses’ and ‘skin-like gold.’ A plethora of kindred literature echoed similar epithets, especially in the Shringarashata composed by Bhartihari, a beautiful complexion akin to skin colour’ eclipsing gold’s lustre.’ North India and South India had distinct cultural connotations of what constituted beauty but never was homogenous.

Jayadev’s Gita Govinda, works of Kalidasa, and the mercurial sage Vatsyayana’s erotic treatise, the magnum opus Kamasutra, celebrates ‘Ujjwala Shyam Varna’ or glistening dark-complexion as the epitome of beauty.

In a 1910 marriage advertisement that appeared in Calcutta newspaper, mentioned in the works of historian Rochona Majumdar, the bride is described as ‘of medium complexion and good figure.’

Ibn Battuta, the legendary traveller and explorer, exclaimed on seeing the ruling Zamorin king of Calicut that he hadn’t seen anyone darker. In his travelogues in India, Marco Polo writes:

For I assure you that the darkest man here is the most highly esteemed and considered better than others who are not so dark. Let me add that in very truth, these people portray and depict their gods and their idols as black and their devils as white as snow.

Ancient aristocracy was tantamount to being dark and, therefore, handsome.

During the Muslim rule in India, commencing with the Delhi Sultanate and followed by the Mughals, fairer skin artworks characterising noblemen of the court were widely disseminated owing to the fairer complexion of the invaders. An alternative cultural milieu evolved that encompassed a self-perpetuating bias towards the notion of fair being beautiful.

Yet, colourism was not institutionalised and politicised until British imperialism, when Indian citizens were relegated to second-class citizens in their own country. Indians were prohibited from holding high administrative offices; dark-skin individuals were barred entry into social clubs, and manifest bias was meted out to light-colored Indians in clerical jobs.

The British further stratified the society by inflaming and entrenching the caste system as a structural reality. The emergence of the pseudo-science of ‘Social Darwinism’ asserted white supremacy and equated ‘whiteness’ to superior intelligence, leadership skills and high moral values. This imaginary social construct also vindicated the vile policies of the imperial British Empire of subjugation and ill-treatment of dark-skinned natives in all their colonised lands.

The institutionalised segregation of dark-skinned people by the British has left an indelible mark and a dark legacy on the psyche of the masses. It still haunts and taunts a majority of the Indian population, emotionally bludgeoned and intellectually capitulated by the reprehensible vestige of the British Raj, which is the collective consciousness condoning colourism.

Franz Fanon, the Francophone, Afro-Caribean political scientist and psychiatrist, in his monumental works, ‘Black Skin, White Masks’ and ‘The Wretched of the Earth, presents a psychoanalysis of the deleterious effects of colonisation, not only on pervasive local culture but also how this renders a condition of subordination of the psyche of the colonised, subverting dignity and self-respect.

Critiques of colonialism have termed the continuing post-colonial subservience to spurious ideals and standards of the former coloniser — which they employed as tools to annihilate the mind space — as ‘Epistemological Colonialism.’

Fanon describes the plight of the colonised people as those ‘in whose soul an inferiority complex has been created by the death and burial of its local cultural originality.’ The colonialist propaganda of white supremacy effectively supplanted millennium-old indigenous cultural markers, causing the colonised to envy their ‘engineered’ cultural superiority and deriding their own.

Edward. W. Said, the Palestinian-American public intellectual, philosopher and academic, in his seminal work, ‘Orientalism,’ has espoused the false stereotyping of Middle Eastern people, by Western academics and historians, based on romantiziced yet racist tropes. He writes in trenchant verses:

“Arabs, for example, are thought of as camel-riding, terroristic, hook-nosed, venal lechers whose undeserved wealth is an affront to the real civilisation. Always there lurks the assumption that although the Western consumer belongs to a numerical minority, he is entitled to own or expend (or both) the majority of the world resources. Why? Because, he unlike the Oriental is a true human being.”

This ‘othering’ has been imbibed in most post-colonial societies. One of its vicious forms — segregation of fellow citizens based on skin colour — triggers preconceived notions of social class hierarchies.

The impregnable culture of arranged marriages in India further accentuates the colonial legacy of colourism. A standard advertisement in the matrimonial section serves as a case study on Indian consciousness and bias towards skin colour. The colonial legacy is zealously perpetuated in these ads, which read:

Hindu, Khatri boy, 30 years, settled in the US, hailing from ancient family seeks suitable alliance from fair-skinned, beautiful and educated girls of similar economic background.

This sexual selection need has ruefully permeated to all castes, societies and communities pan-India. The perception of ‘whiteness’ associated with forward social class, intellectual prowess, educational credentials and economic status is irredeemably entrenched in the Indian subcontinent.

The normal functions of the average Indian skin — namely oil production, wrinkle formation, blemishes and dead cells — became nature’s villainy that warranted meticulous care and attention to reverse skin colour deterioration and diminishing fortunes.

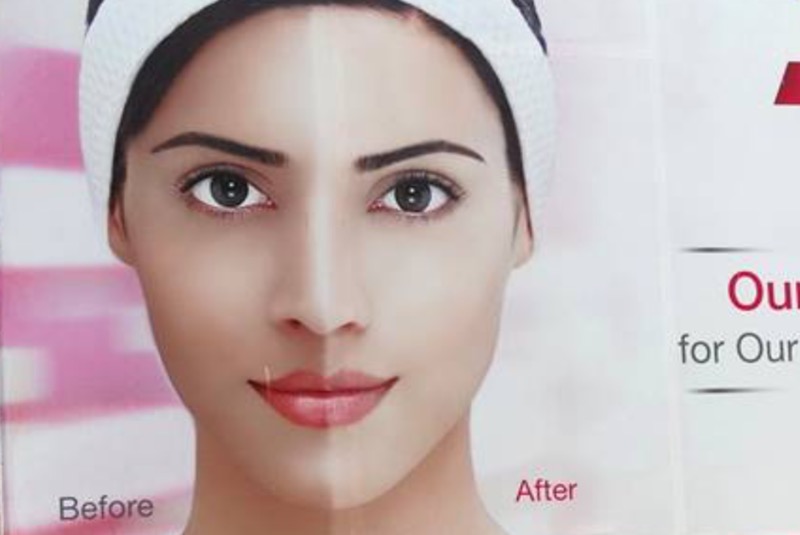

One of the most enduring symbols of colourism and the ‘engineered’ social identity it perpetuates, is a skin-whitening product advertisement from the house of FMCG giant Unilever.

Marketed as ‘Fair & Lovely,’ this ubiquitous beauty product has attained a cult following, capitalising on the insecurities of the average Indian woman. A misogynist and sexist advertisement that ran for several seasons portrays the consternation of a father whose daughter (he wished for a son) – the sole breadwinner – is only having a modestly paying job, and the struggling finances overburden them. The daughter is of a dark skin complexion. The father is seen lamenting, ‘if only we had a son.’

The distraught girl, who overhears him, is gifted by her mother a tube of Fair & Lovely as the panacea for all their ills. Using the beauty product, the daughter transforms into a white beauty, securing a high-paying job. The pernicious insinuation is the pre-requisite of altering inviolable aspects of one’s identity, like skin colour, to have any socioeconomic mobility.

Since the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement and protests sweeping across the US and the world, Unilever rebranded this product by dropping ‘Fair’ into ‘Glow’ and now it is ‘Glow & Lovely,’ in the pretext of making the marketing campaign more inclusive and sensitive catering to all skin-tones and racial types.

Anne McClintock, the Zimbabwean-South African author and feminist scholar, in one of her scholarly articles, Soft-Soaping Empire: Commodity racism and imperial advertising, recounts that the overarching slogan of Unilever in the nineteenth century was, ‘Soap is Civilization,’ alluding to its redeeming power in creating ‘white’ modelled civilisations?

Bollywood, modelling agencies and fashion shows in India have a symbiotic relationship with the high priests of capitalism and globalisation in perpetuating colourism. The common heroine stereotypes reflect the enforced beauty ideals of fair skin, and the protagonists are ethereally beautiful on-screen, unrealistically stunning with slim figures, perfect hair and skin.

Capitalism sets the bar higher for every generation in terms of beauty standards. The proliferation of social media has engendered a phenomenon called the Instagram Face – flawless faces and hour-glass bodies endorsed by celebrities and socialities – that becomes the coveted model for the dark-skinned average Indian women to emulate and aspire to.

This phenomenon results from ‘late capitalism,’ a term coined by Werner Sombart, the German economist and historian, in his three-volume manuscript, Der moderne Kapitalismus.

In late capitalism, the era we inhabit, culture itself is relegated to a commodity. Its derivative beauty products are bought and sold in the overcrowded marketplaces of uncertainties, poor self-esteem and vulnerabilities.

Capitalism and globalisation are just taking a position in the market, segmenting, targeting and positioning (STP) their product offering to reap profits. Their accountability ends with shareholder capitalism, maximising shareholder wealth at the expense of protracted damage done to the wider stakeholders, adversely impacted by the marketing campaigns and cultural trendsetting.

Successful models in the Indian modelling and fashion industry are almost exclusively fair-skinned and often break into Bollywood movies, returning as brand ambassadors of skin-whitening products.

These celebrity endorsements reinforce colourism, ageism, sexism, and racism, redefining gender norms and beauty standards. In this context, it is commendable that dusky actresses like Nandita Das have joined the campaign ‘Dark Is Beautiful,’ launched by an activist group, Women Of Worth, in 2009 to create awareness of true beauty, transcending colour.

This assumes a spiritual dimension leading to the sublime knowledge that the best part of a woman is not her skin or body but the quality of her intellect and the strength of her personality. Her true empowerment lies in liberating herself from all inner enslavements.

Mohammed Ali, the legendary pugilist and intrepid human rights fighter, brought home the global infatuation with white skin in one of his most characteristic touches of sarcasm. During a 1971 interview with Sir Michael Parkinson of the eponymous chat show Parkinson, Ali reminisced about his childhood, being innately inquisitive, asking his mother about the over-representation of whiteness in culture and social mores.

His confused volley of questions included: ‘Mother why is everything white?,’ ‘Why is Jesus white with blonde hair and blue eyes?,’ ‘Why is the Lord’s supper all white men?,’ ‘Angels, Pope and Mary are all white,’ ‘Why Tarzan being the king of the jungle in Africa is white?’, ‘Why Miss America, Miss World and Miss Universe were always white?’ ‘Why everything bad was black?,’ ‘Why the little ugly duckling was a black duck?,’ ‘Why black cat only brought bad luck?,’ and why threatening is called ‘blackmail,’ rather than ‘whitemail’; hilarious yet enlightening.

Perhaps the best answer to Ali’s questions on white obsession came from Robert Mugabe, the erstwhile President of Zimbabwe. He quipped in his quintessential humour:

Racism will never end as long as white cars are using black tyres; if people still use black to symbolise bad luck and white for peace, if people still wear white clothes at weddings and black clothes at funerals; as long as those who don’t pay their bills are blacklisted and not white-listed. But I don’t care as long as I am using the white toilet paper to wipe my black ass.

Imitators always flounder at the crossroads of originality and authenticity and will ever be condemned as imposters, chasing futile horizons that will forever outrun.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]