Diseases change the way we think, feel and experience life. Diseases like Polio, smallpox, Tuberculosis, Malaria, COVID-19, and Monkey Pox have had a devastating impact on human societies. They fundamentally changed the way societies function.

Diseases have also led to incredible advances in medicine. Humans who took on the challenge of finding cures for diseases advanced the field of medicine and made history. Point in case: Polio.

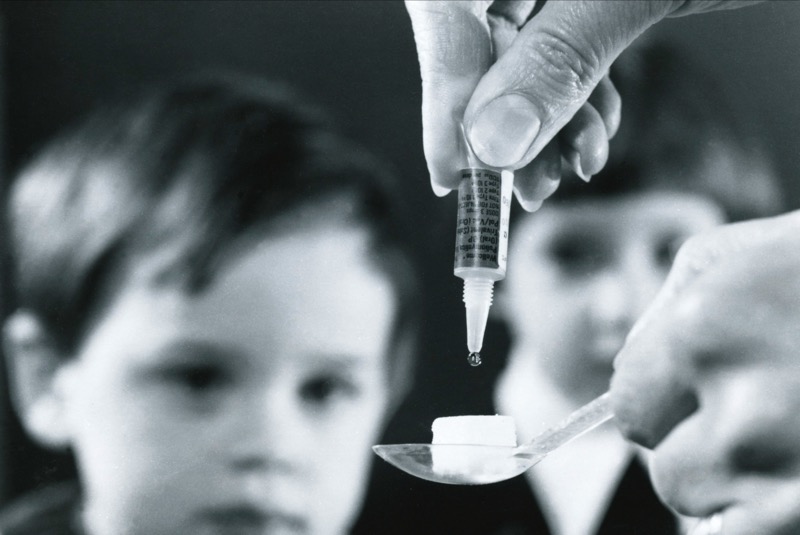

Very few countries still have poliomyelitis, commonly known as polio. India is not one of them. The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared India polio-free on 27 March 2014. It took years of sustained campaigns for the government to vaccinate people and eradicate polio. Many governments have made similar efforts across the world.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recently partnered with UNICEF to end polio in Afghanistan, with the support of the Taliban. Now, United Nations agencies are conducting a large-scale campaign of vaccinations against polio in the Gaza Strip, where the disease has re-emerged, hoping to prevent an outbreak in the territory ravaged by the Israel-Hamas war.

None of this would have been possible without the perseverance of the scientists who invented the vaccine. Polio as a disease was not as common in the 1800s. But in the 1900s, children below the age of five contracted polio very frequently. Almost every summer, many children suffered from polio. While some were able to recover completely, many of them ended up being paralysed.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the thirty-second President of the United States, also suffered from polio. In the summer of 1921, he contracted polio at the age of thirty-nine. President Roosevelt ensured that no one knew about his sickness throughout his presidency. However, he started the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIS) to help fight polio; it is now known as March Dime.

In the early 1950s, Jonas Salk created the first vaccine for polio. He received a grant from the NFIS to research the vaccine. However, three pairs of hands did significant work for Salk in developing the vaccine.

John Franklin Enders, Thomas Huckle Weller and Frederick Chapman Robbins created the strain of the virus inside the laboratory by themselves. Their discovery accelerated the cure for the virus and earned them the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1954. Jonas Salk used their method to create the strain for the vaccine.

John Enders was the senior of the three who worked on creating the strain. Enders hadn’t planned on becoming a scientist since childhood. He went to Yale University to earn an Arts degree. He worked for a while in real estate, a job that failed as soon as it started. Then, he tried to become a teacher. He went to Harvard School of Sciences and Arts to learn literature. But while he was there, he felt all of it was meaningless—until he met Hans Zinsser.

Enders’ friend Hugh Ward was a medicine student. He once took Enders to a bacteriology lab at the university. Here, he saw Zinsser in his element. Enders was almost immediately entranced by Zinsser. He left his PhD in literature but pursued a doctorate in immunology and bacteriology under the guidance of Zinsser. He also earned a PhD in microbiology.

Before contributing to the polio vaccine, Enders created the vaccine for feline distemper with a gentleman named William Hammon. He kept working towards creating viruses in the laboratory and communicated the enthusiasm of his findings to his students. One of these students was Thomas H. Weller.

Wellers’ father was into biology, and his grandfather worked with medicines. He, therefore, saw only these two options as career choices. He could not pick between the two, so he chose a middle ground—parasitology. After completing his bachelor’s degree in Michigan, he entered Harvard Medical School.

Wellers, who was already interested in tissue culture and fascinated by Enders’ work, took a particular interest in the roller tube technology for cultivating tissues—a technique created by Enders. He praised Enders to his roommate Frederick Robbins. Frederick Robbins was into biology because it was not physics, chemistry, or botany—subjects his father wanted him to do.

Robbins ended up being interested in virology because of Weller, who was interested in it because of Enders. Except that the second world war separated the three of them. Although during the war, all three were working with viruses in one way or another. Enders especially worked towards cultivating the mumps virus in the laboratory. He failed, but he did infect a monkey with the virus and was able to create a vaccine for it.

After the war, all three were back together. After all he had heard from Weller, Robbins was delighted to meet Enders. He also received a grant from the NFIS to work on viruses. However, NFIS demanded Robbin work with Enders for only one year. Robbins was happy as long as he got to work with Enders.

During this time, they weren’t as inclined to study poliovirus. They just had it in the back of their minds. They saw that the virus presented itself in large quantities in the faeces of those infected. This made them think that if they combined human embryonic skin with muscle tissue in a suspended cell culture, then the virus could multiply. Fortunately, the virus did multiply, and they succeeded in cultivating it in a laboratory flask.

No one knows which of the three initiated the work or who came up with the idea. All we know is that one assistant professor and his two starry-eyed students came together to cultivate the poliovirus in the lab, paving the way for eradicating polio.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]