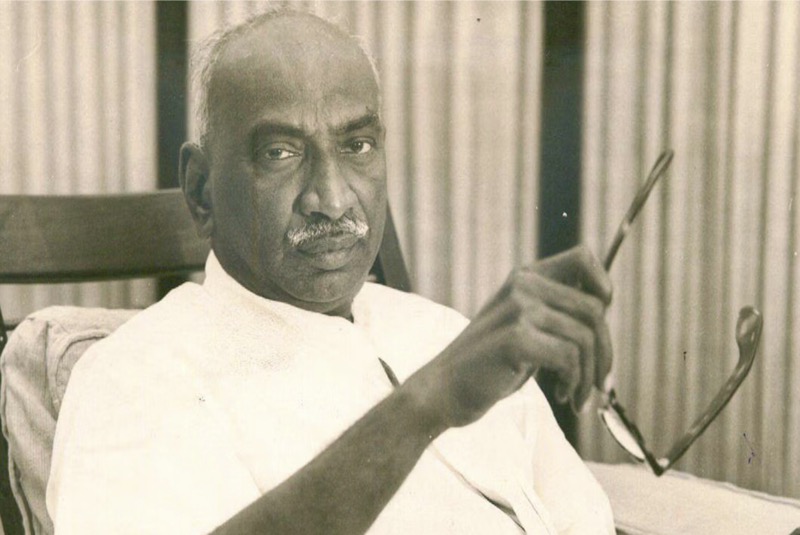

A statue of Kamaraj stands tall at Chennai’s Marina Beach, with two young students standing by him on each side. Kamaraj’s contribution as the Chief Minister of Madras State (now Tamil Nadu) is honourable. He worked tirelessly to enforce efficient leadership of a developing nation, so much so that he was known as a “kingmaker.”

However, the statue at Marina Beach commemorates his influence on education. K. Kamaraj is considered solely responsible for raising the education rate of Tamil Nadu to 85 per cent during his decade of leadership.

When Kamaraj took the seat as the Chief Minister of Madras State on April 13, 1954, he pioneered accessible education for the poor and needy. With compulsory education, new school construction, free uniform distribution, and syllabus revisions, Kamaraj became popular as the ‘Father of education.‘

While visiting Cheranmahadevi town in Tirunelveli district in the early 1960s, Kamaraj saw a boy grazing cattle at the railway crossing and asked him why he was not in school.

“If I go to school, will you give me food to eat? I can learn only if I eat,” the boy said to Kamaraj.

These words inspired Kamaraj to introduce one of his most popular policies–the Mid-Day Meal Scheme.

Kamaraj was born in a merchant family. After his father passed away, his mother struggled to meet ends. At the tender age of 11, Kamaraj had to drop out of school to support her.

Maybe his childhood created empathy for the kid at the train intersection, but Kamaraj knew the importance of education. He also understood that it was an unaffordable luxury for many impoverished families. However, a solid meal a day could incentivise school and increase attendance.

Kamaraj and Sundara Vadivelu, Director of Public Instruction (DPI), attended a meeting in Madras on March 27, 1955. Kamaraj was interested in learning about the effect of mid-day meals given to students in Madras municipality schools and Harijan welfare schools.

DPI stated that attendance from Mondays to Fridays was twice as high as on Saturdays. Since schools on Saturdays were only open for half-days, lunch was not provided. His statistics-based argument to Kamaraj demonstrated the need for mid-day meals.

It was the beginning of the Second Five Year Plan (SFYP); financial transfers from the Central Government to the State Governments were based on the forecasts for different programmes from the individual State Governments. Mid-day lunches for all primary school students, on the other hand, were not a feasible proposition to the Central Planning Commission.

Kamaraj’s determination and perseverance in realising the noon meal programme was evident in his talks with Planning Commission officials. DPI was even compelled to agree to abandon the mid-day meals plan in favour of other numerous short-term welfare measures to the State. The mid-day meals programme was deemed untested on a big scale, and the difference between available and needed funds was a whopping five crores (50 million Rupees).

However, Kamaraj was prepared to levy a new tax to implement the mid-day meals programme. After much convincing, the SFYP included the mid-day meals programme for funding, and the Legislature also approved the concept.

On March 27, 1955, an announcement was made regarding the plan. The Director of Public Instruction launched the mid-day meals programme at Ettayapuram, Tirunelveli District, on July 17, 1956.

From November 1, 1957, the Kamaraj Government extended the programme to include as many primary schools as feasible using available Central Government funding. The scheme’s success, however, can be ascribed mainly to public contributions.

The government’s contribution was just ten paise per kid, with a possibility for a five paise contribution from local authorities, which was often unavailable. As a result, the program’s continuation largely depended on volunteer contributions.

Kamaraj travelled extensively throughout the State, speaking to the public during conferences, meetings, and even one-on-one discussions. He stressed the mid-day meals scheme needed to be implemented in schools as soon as possible, and it was an individual social responsibility to feed the children of their society.

Locals organised and established committees to use the money and items effectively. Nonmember secretaries of these committees were usually the Head Masters of schools. Local committees bore the entire cost of non-recurring goods like kitchenware.

Under Kamaraj’s plan, about 20 lakh primary school students in grades I through VIII were fed for 200 days each year. The kids came to school for hearty cooked rice and sambar meals complemented with buttermilk or curd and pickles.

From July 1961 onwards, the ‘Cooperative American Relief Everywhere’ (CARE) shared the economic burden of the mid-day meals programme on the government. They began supplying food supplies, such as milk powder, cooking oil, wheat, rice, and other nutritional goods.

Though initially seen as a populist tactic, the mid-day meal policy gained traction as school enrolment and attendance increased. It ultimately received backing from the Central Government and was a remarkable success in only five years. Between 1957 and 1963, spending rose seventeen times, resulting in a six-fold rise in the number of children who benefited.

Children from low-income families who had been kept out of school began attending school, as it ensured at least one nutritious meal per day for the child. Dropouts who left school to support their families decreased significantly. Children’s concentration improved due to the programme since they were no longer hungry during class.

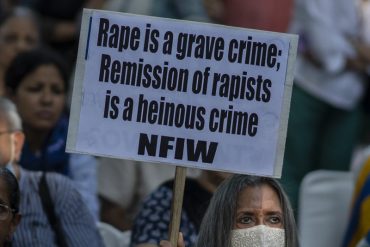

The mid-day meal scheme promoted unity among kids. Children from various backgrounds sat together and ate the same meal, forming a fraternity. To some degree, it promoted the abolition of caste boundaries in the minds of young people.

Kamaraj’s mid-day meal scheme was a hit. M.G. Ramachandran expanded the initiative during his term as chief minister in 1982, and soon the Central government adopted it. It is now the world’s biggest schoolchild feeding programme, serving 11 crore kids in 12 lakh schools.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]