“Singh was a nice sort of person, cultured, kind…. It was very enjoyable to be with him…. He was calm and patient and knew how to look at things with a certain sense of humour….He came to live with us, and to Katya and I, he was our mother’s husband, and we treated him with respect. I think she was happy.”

Svetlana Alliluyeva was Joseph Stalin’s only daughter and “the little princess of the Kremlin,” as she was known. The quote above is a testimony of his son, Joseph, who talks about Alliluyeva’s greatest love affair and the Soviet Union scandal.

In October 1963, Svetlana was admitted to the Kuntsevo Hospital for tonsillectomy. To beat hospital boredom, she was reading Gandhi’s biography. So, when she saw “a small, stooped, grey-haired man” of Indian descent roaming about the hospital, she immediately wanted to approach him and ask him about Gandhi.

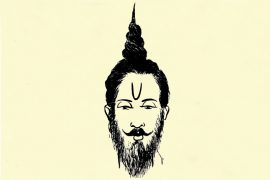

Brajesh Singh, who belonged to the Kalakankar royal family, had been living in Russia since the 1930s. When he met Svetlana, he was being treated for bronchitis and emphysema. The two bumped into each other and shared a deep conversation sitting on a hospital couch. Singh asked Svetlana which organisation she belonged to, and she said: “None.”

Brajesh was in London in 1932 when he turned to communism to fight for India’s independence. However, when he met Svetlana, he no longer identified as the fervent communist he used to be. He did not even know Svetlana was Stalin’s daughter. Even when he did find out, his only response was “Oh!”

Singh never showed much interest in knowing about Stalin. However, at the age of fifty-three, Singh was impressed with thirty-seven-year-old Svetlana, who thought for herself. Svetlana was enamoured by the man with a calm demeanour and rich spirituality; she would invite the man to live with her and would call him her husband until the day he died.

Svetlana had been married three times before, and Singh had married twice. Singh’s health was in shambles and slowly deteriorating; however, the couple had been eager to find love and companionship. At first, Svetlana wanted to fulfil her fantasy of marrying the man she loved; she wanted to travel the world with him, but it was also a matter of urgency.

Marriage was the only way for Singh to be protected from expulsion and to get Soviet citizenship. If Singh were to go to India, Svetlana needed to be his wife to travel with him. However, politics had always shaped Svetlana’s life, keeping her from being free and making her own decisions, and even this issue stood as an obstacle.

The day after she had tried to register her marriage with Singh at the Moscow office, she was summoned to the Kremlin. She met with the chairman of the Council of Ministers, Aleksei Kosygin, newly elected with the conservative communist party that came back in power after the fall of Nikita Khrushchev.

In Svetlana’s record of the meeting, when Singh is mentioned as her ‘husband’, Kosygin turns red with anger.

“What have you cooked up? You, a young, healthy woman, a sportswoman, couldn’t you have found someone here? I mean, someone young and strong? What do you want with this old sick Hindu? No, we are all positively against it, positively against it,” he said.

Svetlana and her lover were never allowed to marry. The pair witnessed the rise of the orthodox Communist Party in horror. Svetlana condemned the hypocrisy with which the government was curbing the opposition by fear and oppression. She was tired of all the politics; she was tired of her connection to her father.

In late 1966, it was clear that Brajesh was terminally sick. He was admitted to Kuntsevo Hospital, where Svetlana would spend most of her time tending to him. He wanted to go to India and spend his last days in his home country, but not without Svetlana. Svetlana wrote to the government, begging to let them go, but all she received was apathy.

She was summoned to the Communist Party Headquarters on Old Square, where she asked for permission to get married again. Mikhail Suslov, the Party’s chief ideologue, told Svetlana that her father had established a law against marrying foreigners, and it was unpatriotic of her to leave the country and go to India.

On 30 October 1966, Brajesha was discharged upon his request. He wanted to go home. When the couple was alone at home, Brajesh told Svetlana of a dream in which he saw a white bullock pulling a carriage. He said the dream was a premonition of his death. Svetlana did not believe it, but at seven in the morning the next day, Brajesh said he could feel a throbbing in his chest and his head. Then, Brajesh passed away.

Svetlana made sure Brajesh received a proper Hindu funeral, with his body cremated as he deserved. He had expressed his wish to have his ashes scattered in the Ganges, although he never thought that would be possible. Svetlana promised to make it out of the country somehow and scatter his ashes herself.

Due to diplomatic measures, Svetlana was allowed to make the trip, as Brajesh’s nephew, a politician himself, had secured a traditional funeral from Indira Gandhi. Brajesh, who had promised to bring her to his village, Kalakankar, was now gone, and in his place, next to Svetlana on the aeroplane, sat his urn.

Svetlana had thought of her father’s dying days, bitter and full of struggle. She compared it to Brajesh’s last days, quick and full of peace. “Each man got the death he deserved.”

After completing Brajesh’s rituals in his village, Svetlana stayed in Delhi at the Russian Guesthouse. She was always the centre of attention and was constantly advised by the officials to return to Russia. On the night of the International Women’s Day party, 6th March 1967, which had engaged all the Russian officials, she snuck out of the guesthouse and called a taxi. She nervously waited with fearful thoughts of what might happen if she was caught. When the cab arrived, she asked the driver, “Do you know the American Embassy?”

Once she reached the Embassy, she climbed the staircase with shaky legs to meet the guard who tried to tell her off as the embassy was not open. Once he found out who she was, he led her in, sat her down, and rang up Ambassador Chester Bowles. Svetlana wrote down her intent to defect on a lined pad. She was sent to Rome with an open ticket the next day, only after which her news of denouncing Communism reached Russia.

Swetlana would face a tumultuous week where different countries questioned and debated her refugee status. Finally, in the early morning of 11 March, Svetlana “stepped over the invisible boundary between the world of tyranny and the world of freedom.”

The daughter of Stalin, the “state property,” as she referred to herself, was on a journey that would divide her life into a before and after. Her defection to the United States was a huge political sensation. It would be 18 years before she could see her son.

“I did not dream what epilogue that journey would have,” Joseph had remarked.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]