India’s history is often told through the lens of its regional identities, distinct cultures, and rich linguistic diversity. India’s states are carved along such lines, where language is not just a mode of communication but a defining feature of personal and collective identity. The country’s constitution recognises “official languages,” each a bearer of unique traditions, oral histories, and philosophies.

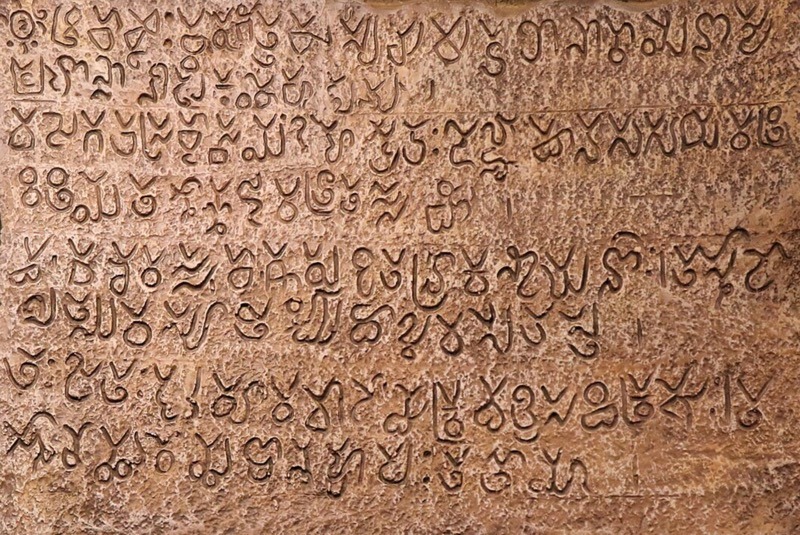

Among them is Telugu, a language that stands out not just because of its status as one of the oldest Dravidian tongues but also because of its extraordinary legacy. Spoken by millions, it is the third-most spoken language in India and the fifteenth in the world. Its roots trace back to the third millennium BCE, long before the world began to carve the land into the nations we recognise today.

The name “Telugu” is steeped in mythology, derived from “Trilinga,” which refers to the land of three sacred lingas. According to Hindu tradition, these were where Shiva, in his divine form, descended upon the earth. The three locations—Kaleshwaram in Nizam, Srisailam in Rayalaseema, and Bhumeswaram in Kostha—are deeply venerated in both religious and cultural contexts, contributing to the deep reverence for the language and its speakers. Yet, what makes Telugu particularly fascinating is not merely its antiquity or religious associations, but its surprising similarities to a language far removed from it in both geography and linguistic family: Italian.

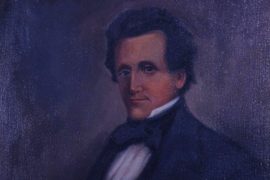

How could a Dravidian language, rooted in the subcontinent of Asia, share similarities with an Indo-European tongue like Italian? This question puzzled Niccolò de’ Conti, a Venetian merchant whose travels to India would forever alter how Europeans viewed the Indian subcontinent. De’ Conti, a keen observer of the world, sought not just riches but knowledge. He was one of the first Europeans to journey extensively across Asia, reaching as far as the southern empire of Vijayanagar, where he became fascinated with the local language, Telugu. His interest wasn’t sparked merely by curiosity but by a remarkable discovery: that Telugu, with its regressive vowel harmony, bore a striking resemblance to Italian, a language he knew well.

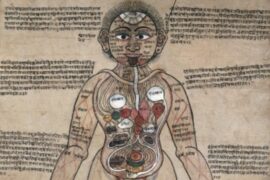

De’ Conti’s observations are a testament to the intersections of trade, culture, and language. Relations between India and Rome date back to the first and second centuries. Though the two empires were worlds apart, they were not entirely disconnected. Southern India, with its riches in spices, gemstones, and textiles, was a key player in the global trade networks that spanned the ancient world.

Rome’s engagement with India, particularly its trade with the Tamil-speaking regions of the subcontinent, was so intense that it eventually sparked the interest of Roman intellectuals, who sought to learn more about the faraway lands. But it wasn’t just the allure of wealth that drew Europeans; there was also a profound fascination with India’s intellectual and cultural advancements, which were becoming known to Europeans through travellers like de’ Conti.

De’ Conti’s travels were legendary. He ventured far beyond the territories of the Ganges, navigating the coastlines of India and reaching the island of Taprobana (modern-day Sri Lanka). His reports, translated and disseminated in Europe, were among the first to offer detailed descriptions of Indian customs, landscapes, and people.

His account of the “Sati” practice, the training of elephants, of Hindu customs, and the technological marvels he encountered—particularly the shipbuilding methods in use at the time—gave rise to a fascination with the “exotic” East. However, his encounter with Telugu remains one of the most remarkable aspects of his journey.

While in the court of Krishna Deva Raya, a king renowned for his patronage of the arts, de’ Conti was introduced to Telugu in earnest. Krishna Deva Raya, himself a scholar of the language, surrounded himself with poets, musicians, and intellectuals. It was here, amid this vibrant cultural milieu, that de’ Conti began to study the language, and much to his surprise, he found it remarkably accessible.

What struck him most was the harmony of its structure, the way words seemed to naturally flow and end in vowels, much like the melodic cadences of Italian. This regressive form of vowel harmony, a hallmark of many Dravidian languages, mirrored the rhythmic, vowel-centred sounds of the Romance languages. In this, de’ Conti found something profoundly compelling: the possibility of a distant, yet uncanny, linguistic kinship between two cultures separated by vast oceans and even vaster cultural divides.

De’ Conti, in his reports to Pope Eugene IV, would go on to call Telugu “the Italian of the East,” a striking and somewhat poetic observation that has lingered in the collective imagination ever since. His fascination with the language was more than just linguistic. It spoke to something deeper: the ways in which distant civilisations, with their separate histories and cultural practices, can nonetheless find echoes of one another in the most unexpected places.

The idea that two languages, stemming from entirely different linguistic families, could share such structural similarities was nothing short of astonishing. What did it say about human cognition, about the ways languages evolve and adapt, about the ways cultures find common ground even when they seem so vastly different?

These questions were far from theoretical for the people of the Indian subcontinent. In the same way that de’ Conti was fascinated by the language and culture of India, the Indians of that time had their own understanding of the Europeans who, by then, had begun to enter their shores. Their perceptions were shaped by their own social, intellectual, and religious frameworks.

While the Europeans may have looked upon India with a mixture of awe and curiosity, they were also viewed through a complex lens that included reverence, suspicion, and, at times, disdain. It wasn’t until the British began their colonial ventures that European influence began to reshape Indian society in more profound ways. But before that, the interactions between the two worlds were more sporadic, marked by moments of fascination and the exchange of knowledge and ideas.

De’ Conti’s discovery of the linguistic similarities between Italian and Telugu was one thread in a vast, intricate tapestry of cultural exchange that spanned centuries. His writings contributed to a growing awareness in Europe of the intellectual richness of the Indian subcontinent; they also prompted Europeans to grapple with the fact that the world beyond Europe was not only ancient and complex but also deeply connected in ways that defied the linear histories they had imagined.

Through the lens of language, art, and culture, the peoples of India and Europe found themselves bound together, not just by trade and exploration, but by a shared, if often unacknowledged, history of mutual discovery.

The voyages of Niccolò de’ Conti, and the relationships that flourished between Europe and India in the centuries to come, were more than just encounters of curiosity. They were the beginning of a dialogue that would continue to shape both continents in ways neither could have anticipated.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]