Racism has laid the groundwork for the police brutality Black Americans experience every day in the United States. Racism also explains the violent suppression by the military and the militarized police of peaceful protests across the country demanding justice for Black lives, when climate protestors have never experienced such brutality.

But racism also brought us the climate crisis. The reality is that the significant impacts of the climate crisis on vulnerable communities are happening because our country was willing to sacrifice Black, brown and indigenous lives by placing polluting and extractive facilities in Black, brown, and indigenous communities in the United States and around the world. The climate crisis is, at its core, a racial injustice crisis.

In my community in Washington, DC the most polluted zip codes are in Black communities. Highways run closer to homes east of the Anacostia River, where we have the highest density of Black neighbors. Asthma ratesin the Black community are double that in the Caucasian population in DC, following the national trend. Black Americans are three times more likely to die from pollution nationwide. With the global coronavirus pandemic, Black Americans are four times as likely to test positive with COVID-19, and studies also show that death rates from COVID-19 are higher in areas with dirty air.

Indigenous communities in the United States are just as likely to be treated as sacrifice zones, sadly, given that all of this land is stolen from tribes. The Navajo and Hopi tribes have some of the highest per-capita cases of COVID-19. I recently participated in a human rights tribunal for the Carrizo/Comecrudo tribe in South Texas, hosted by the Gulf Coast Center for Law and Policy, and learned about plans to build a fracked gas export facility on sacred land that could be a burial ground.

The tribunal documented ongoing violations of indigenous sovereignty, violence and environmental degradation, including a crisis of missing indigenous women that is linked to “man camps” that form around fossil fuel extraction facilities. The Carrizo/Comecrudo tribe is just one example of these violations. As we know from Standing Rock, the Keystone XL pipeline struggle and extraction on Navajo land, across the United States, sovereign tribal land has been poisoned by pipelines, mining, and coal.

But it’s not only in North America. My parents were born in Bengal, which now stretches across both India and Bangladesh, thanks to colonialism. My family in Kolkata – like so many others in India and Bangladesh – are suffering from the climate crisis today, as they are reeling from Cyclone Amphan and its devastation, which forced people to seek shelter during a global pandemic.

Public opposition is enormous to the Rampal coal-fired power plant planned inside the UNESCO world heritage site of the Sundarbans in Bangladesh, but the government insists it is needed to fuel the economy, including the fashion export industry.

Bengal is just one of many places around the world that is the home of exported pollution or extraction, and also suffering the tragic consequences of the climate crisis at the same time. Bengal might be in a better place to protect people if it wasn’t for famine, partition, wars caused by colonialism rooted in racism.

A study last year published in the Journal Geophysical Research Letters showed that the 1943 Bengal famine which killed 3 million people was not caused by drought. That analysis casts the disaster in a different light – not as a climate crisis, but as a racist crisis caused by British colonialists and Winston Churchill’s policies.

Arm In Arm

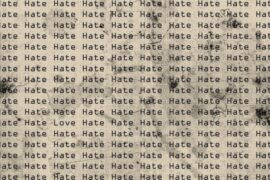

Indigenous, Black and brown communities around the world are more vulnerable to climate change because of racism that sees them commonly located near belching factories, smog-filled highways, exploding pipelines and other extractive infrastructure driving the climate crisis. Richer, whiter communities can fight off highways in the midst of their houses, oil and gas pipelines, and polluting factories. Poorer, blacker communities have less power to reject such plans or less choice about where to live – and suffer the consequences.

But today, we are all feeling the impacts of unchecked racism and climate chaos. That is why in the United States, we have launched a movement called “Arm in Arm”, with the goal that our communities ignite a transformational era that ends the climate crisis by putting racial and economic justice at its heart. We are calling on climate activists to conduct acts of “disruptive humanitarianism” in their communities which both disrupt our racist system and provide immediate humanitarian relief.

Any three people can set up a hub of Arm in Arm as long as they commit to being anti-racist and our other principles. Our first call was on May 15, in the middle of a global pandemic, and just in our first weeks, we have already planted fruit trees on public land in Utah to feed the community, shut down 30 streets in Washington, DC to demand slow, bikeable streets for kids and essential workers, passed out food to hundreds of homeless and hungry people in Spokane, Washington and Birmingham, Alabama, as well as posted art and signage in Houston, Texas and across South Carolina drawing attention to our demands for climate justice.

Now we are calling on climate activists across the United States to stand in solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives and participate in their week of action. Today we are launching a petition specifically for climate activists around the world to show and ask for solidarity with Black Lives Matter. We are doing this work not only because it is the right thing to do, but also because the cause of racial justice is the cause of climate justice and the two are so tightly intertwined.

This article was first published by Thomson Reuters News Foundation.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]